Very few people pay attention to the debt ceiling risks, and for a reason. The debt ceiling has been raised 74 times since March 1962. I commented it in the BBC as far as 2013 (here). It is, therefore, logical that investors and citizens believe that it will be raised yet again in September.

Very few people pay attention to the debt ceiling risks, and for a reason. The debt ceiling has been raised 74 times since March 1962. I commented it in the BBC as far as 2013 (here). It is, therefore, logical that investors and citizens believe that it will be raised yet again in September.

These are the possible scenarios:

- The US Treasury waits until the 29th September deadline to announce the payment of debt and warns that it might default on the maturities of the Social Security payments ($25bn) of the 3rd of October. This could force Congress to reach an agreement before the October date. Morgan Stanley gives this option a 45% probability.

- The Trump administration forces the situation to unblock key reforms and approve the 2018 budget (read). It may use the contingency options created in 2011 by the Obama administration that prioritize payments on government securities over other obligations. As such, the US does not default, and all other items of the budget need to be revised.

- The US Treasury believes it has enough resources to pay the October maturities and delays the decision to the 1st November, where there would be no cash to make the payments.

- Congress reaches the conclusion that there will be no agreement on raising the debt ceiling, which would mean approving an extension of the debt to the end of the year. This would limit debt issuances and Morgan Stanley also gives it 20% probability.

Interestingly, many commentators see this debt ceiling debate as a key obstacle for the Trump administration. However, considering that the Mulvaney budget and the opinion of key administration officials is that the debt problem is a “crisis”, it could be a way of implementing budget cuts and balancing measures to curb the deficit and reduce the imbalances of the US economy.

If we think about it, a divided congress is a problem if the administration wants more public spending and more debt. On the opposite side, a divided congress that fails to agree on a debt ceiling increase could be perfect to undertake budget reforms on discretionary spending, which seemed almost impossible under a bipartisan agreement to spend more and increase debt.

The total budget exceeds $3.65 trillion and discretionary budget is $1.244 trillion for 2018. Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid will not be cut as they were created by Acts of Congress, and cannot be cut without another of those Acts.

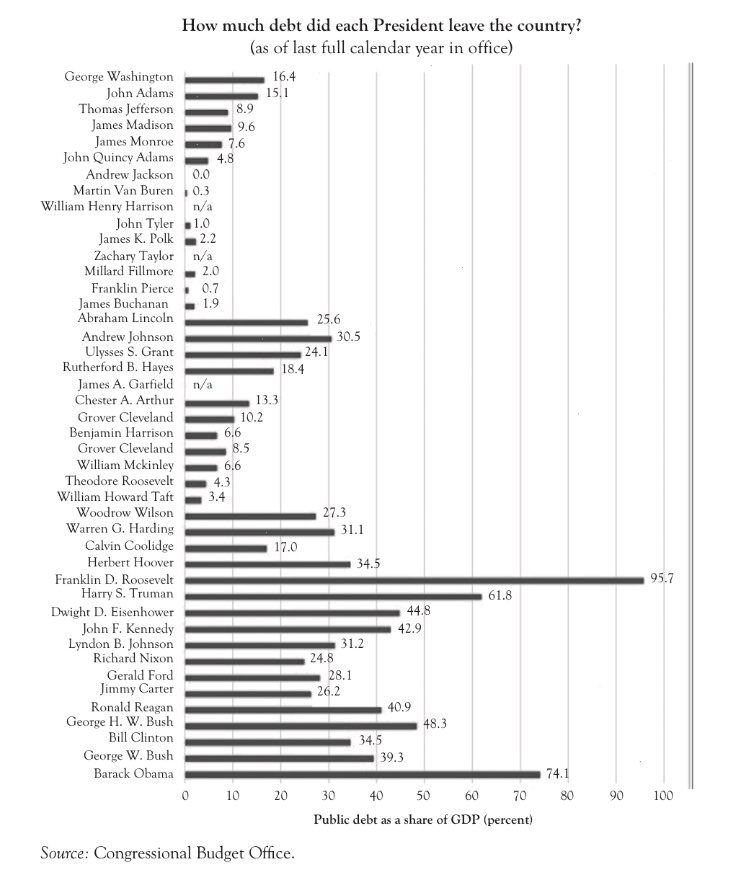

The magic idea that the US can print all the money to avoid default ignores the fact that debt has skyrocketed with monetization, not fallen, while purchasing power of the US dollar has collapsed. Despite interest rates at all-time lows and depressed bond yields, interest federal outlays remain almost at crisis level, $240 billion a year, close to $100 billion higher than in 2003. Even without new spending, the cost of servicing the national debt is expected to nearly triple over the next 10 years, according to estimates by the Congressional Budget Office. That’s more than twice as fast as the growth of spending on Social Security or Medicare, according to CNBC.

The US budget can afford to eliminate the deficit, a $450 billion cut in spending, thus moving into a budget balance. It might mean delaying the defense spending increases, but it would also prevent higher tax increases in the future or a perverse incentive to monetize the debt and destroy the purchasing power of citizens savings and salaries.

Tying any debt ceiling negotiation to a review of non-essential budget items is key.

Whatever happens in September, the US needs to address its debt problem. Monetizing and devaluing has not solved it, only worsened it, and the economy is not stronger due to deficit spending, but less dynamic. Reducing bureaucracy and unnecessary regulation, limiting political power and eliminating duplicate or political expenses, putting more money into the citizen’s pocket should never be bad news. Debt is not free.

Daniel Lacalle is Chief Economist at Tressis, SV a PhD in Economics and author of Life In The Financial Markets, The Energy World Is Flat (Wiley) and Escape from the Central Bank Trap (BEP).

As usual, Lacalle hits the nail, right where it needs to be hit.

Thanks, my friend

The only problem I can see with a balanced budget is the fact that every time its been tried in the past it produces a depression.

I assume, as a PhD, you are aware of that. Perhaps you should tell your readers though.

http://articles.latimes.com/2012/dec/21/opinion/la-oe-kelton-fiscal-cliff-economy-20121221

Balanced budgets do not cause depressions. Look at the Clinton years. That is an absolute fallacy.