The European Central bank has signaled the end of its asset purchase program and a possible rate hike before 2019. After more than 2 trillion euro of purchases and zero interest rate policy, it is overdue.

The European Central bank has signaled the end of its asset purchase program and a possible rate hike before 2019. After more than 2 trillion euro of purchases and zero interest rate policy, it is overdue.

The massive quantitative easing program has generated very significant imbalances and the risks outweigh the questionable benefits.

The balance sheet of the ECB is now more than 40% of the Eurozone GDP.

The governments of the Eurozone, however, have not prepared themselves at all for the end of stimuli.

Rather the contrary.

The Eurozone states often claim that deficits have been reduced and risks contained. However, closer scrutiny shows that the bulk of deficit reductions came from lower cost of debt. Eurozone government spending has barely fallen, despite lower unemployment and rising tax revenues. Structural deficits remain stubborn, and in some cases, unchanged from 2013 levels.

The 19 eurozone countries have collectively saved 1.15 trillion euros in interest payments since 2008 due to ECB rate cuts and monetary policy interventions, according to Handelsblatt. A reduction in costs against the losses of pensioners and savers.

However, that illusion of savings and budget stability can rapidly disappear as most Eurozone countries face massive maturities in the 2018-2020 period and wasted precious years of quantitative easing without implementing strong structural reforms. Tax wedge rose for families and SMEs, while current spending by governments barely fell, competitiveness remained poor and a massive one trillion euro in non-performing loans raised doubts about the health of the European financial system.

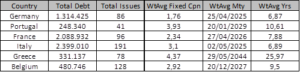

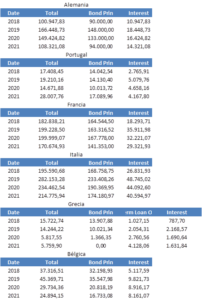

The main eurozone economies face more than 2.1 trillion euro in maturities between 2018 and 2021. This, added to lower tax revenues due to the slowdown and rising spending from populist demands creates an enormous risk of a large debt crisis that no central bank will be able to contain. Absent of structural reforms, the eurozone faces a Japan-style stagnation or a debt crisis.

The ECB warned in 2014 that “many euro area countries did not take advantage of the favorable economic conditions prior to the crisis to build up a fiscal buffer for future downturns”. This is happening again, but much worse, as average debt to GDP has soared to almost 90% and government spending to GDP also remains above 40% with zero interest rates and massive asset purchases. The reality is that the ECB is left without tools to tackle a new crisis through money supply and rate cuts.

Where should bond yields be if the ECB was not the largest purchaser of Eurozone bonds? We do not know for sure, as there is no discernible secondary demand at these levels. At the peak of QE in the US, the Federal Reserve was never 100% of net issuances of treasuries. Today, the ECB program is more than three times the net issuances. This means we have no clue of what is the real market demand for eurozone sovereign bonds and what yields would be demanded by investors.

What we know is that yields would be massively higher. A minimum of 120 basis points above current yields would be needed to reflect the inflation expectations and bring yields closer to the curve.

Of course, the Eurozone nation would not feel the whole increase in expected yields. At the peak of the Euro crisis, Spain’s average cost of debt was 3.4% or almost 300 basis points below where yields rose. But the return of yields to normalized levels will likely affect confidence as the placebo effect of QE vanishes and reality returns.

No single country in the Eurozone except Germany, maybe The Netherlands, is ready for the end of QE.

Eurozone governments have spent all the benefits of QE in higher current spending and kept structural deficits. The entire improvement in net interest expense has been squandered in higher bureaucratic spending.

Now the tide is turning. Even if the ECB decides to delay the end of QE, the reality is that sovereign yields and credit default swaps have been quietly rising. Not just due to the Italian crisis, but due to the evidence of unsolved issues coming back to the surface in Europe.

The worst part of this is that governments in Europe will likely decide to increase taxes to try to tackle rising deficits coming from the evidence of the Eurozone slowdown in lower revenues and the end of zero-interest-rate policies in expenses.

The combination of the already clear slowdown with higher tax wedges, stubbornly high spending and rising deficits and rates can be a perfect storm for Europe that will likely bring back the ghost of the crisis.

Europe decided to tackle the crisis hiding imbalances under a massive wave of liquidity and governments abandoned all reforms to bet it all on monetary policy. Now, the reality is likely to show its face abruptly. And none of the governments in Europe is ready, because they are not even aware of the extent of the problem.

Daniel Lacalle is Chief Economist at Tressis, SV a PhD in Economics and author of Life In The Financial Markets, The Energy World Is Flat (Wiley) and Escape from the Central Bank Trap (BEP)