The main reason why the ECB quantitative easing program has failed is that it started from a wrong diagnosis of the eurozone’s problem. That the European problem was a demand and liquidity issue, not due to years of excess.

The ECB had been receiving tremendous pressure from banks and governments to implement a similar program to the US’ quantitative easing, forgetting that the eurozone had been under a chain of government stimuli since 2009 and that the problem of the euro-zone was not liquidity, but an interventionist model.

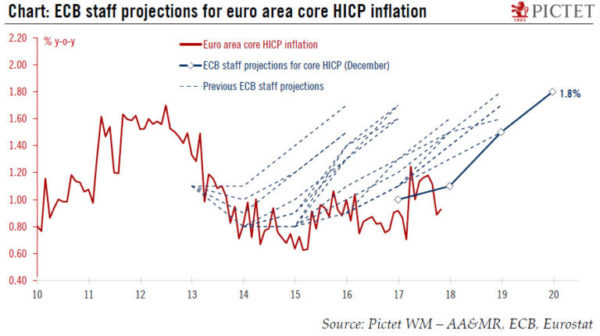

The day that the ECB launched its quantitative easing program, excess liquidity stood at 125 billion euro. Since then it has ballooned to 1.8 trillion euro.

“Only” after 2.6 trillion euro purchase program and ultra-low rates:

Eurozone PMIs are atrocious. The euro-zone index falls from 52.7 in November to 51.3 in December, well below the consensus forecast of 52.8. More importantly, France’s PMI plummeted from 54.2 in November to a 34-month low of 49.3.

Unemployment in the euro-zone, at 8%, is double that of the US and comparable economies. Youth unemployment rate remains at 15%.

Economic surprise has plummeted as the ECB balance sheet reached 41% of GDP (vs 21% of the Fed).

More than 900 billion euro of non-performing loans remain in the banking system, which keeps a trillion euro timebomb in its balance sheets (read). A figure that represents 5.1% of total loans compared to 1.5% in the US or Japan.

Deficit spending is rising. Government debt to GDP has risen to 86.8%.

The number of zombie companies -those that cannot pay interest expenses with operating profits- has soared to more than 9% of all large quoted firms, according to the BIS.

Sovereign states have saved around one trillion euro in interest expenses, but have spent all those savings. Today, almost no eurozone country can absorb a modest rise in interest rates, and Italy, Spain, France, Portugal, Slovenia, and others are demanding more spending and more deficits.

There is no real secondary market demand for eurozone sovereign bonds at these yields. At the peak of its quantitative easing program, the Federal Reserve was never the sole buyer of Treasuries. There was always a relative secondary market. In the Eurozone, the ECB has been 7 seven times the net issuances of sovereigns. No investor is likely to buy eurozone sovereign bonds at these yields once the ECB steps down.

Eurozone growth and inflation estimates have been revised down again in December. Industrial production has fallen sharply.

Trichet, the ECB’s predecessor to Mario Draghi, had lowered interest rates from 5% to 1%, injected billions into the economy, buying sovereign bonds in 2011.

What has the ECB been successful at?

- Keeping the euro alive. Not a small success, by the way. The risk of break-up has been contained but not eliminated.

- Maintaining government spending at low rates. However, at the expense of savers and salaries.

- Generating a sense of euphoria in financial markets, with high yield and sovereign bonds soaring.

- Wages in the euro-zone have increased below inflation since QE launched and into the third quarter of 2018. In fact, low inflation has been the biggest unintended success of the ECB. It could have been worse.

- The biggest “success” of the ECB has been the massive bailout of governments at the expense of savers.

(Courtesy Pictet)

We also have to agree that Mario Draghi has been reminding governments that they needed to implement structural reforms, use the period of low rates to deleverage and repeating constantly that monetary policy will not work without reforms. No one listened. It was party time, and cheap money attracts bad decisions.

A Never-Ending Government Stimulus

With public spending averaging over 46% of GDP, an annual deficit of over 1.7% on average, and 86% debt, talking about austerity is like eating a box of cakes and calling it “diet”.

The tax burden in this period has been raised throughout the EU (with honorable exceptions, such as Ireland) with an average tax wedge of 45% for workers and 40% on companies.

The United States, at the peak of the crisis, spent 43% of GDP (the EU, 50%) and dropped it to 34%, and that with 21% of the budget in 2009 dedicated to defense.

The EU has been a Keynesian stimulus machine before, through and after the crisis.

1) A massive stimulus in 2008 in a “growth and employment plan”. A stimulus of 1.5% of GDP to create “millions of jobs in infrastructure, civil works, interconnections and strategic sectors”. 4.5 million jobs were destroyed and the deficit nearly doubled.

Between 2001 and 2008, money supply in the euro-zone doubled.

2) Two massive sovereign bond repurchase programs with Trichet as ECB President, interest rates down from 4.25% to 1% since 2008. Poor Trichet. Trichet purchased more than 115 billion euros in sovereign bonds.

3) An additional mega stimulus from the ECB, in addition to the TLTRO liquidity programs with Draghi, which has taken sovereign bonds to the lowest yields in history and purchased almost 20% of the total debt of some major states.

The problem of the European Union has never been a lack of stimuli, but an excess of them.

As government expenditure and unproductive investments multiplied, overcapacity remains at levels of 20% and the constant errors of interventionism leave the euro-zone after the biggest monetary experiment in its history with the same high tax wedge and obstacles to the productive sectors.

The end of the ECB QE leaves the euro-zone in a weaker position than it was in 2011. Because fiscal space has been exhausted and the ECB, with its balance sheet at 41% of the euro-zone GDP and ultra-low interest rates, has also exhausted its monetary tools.

The end of QE does not just show the failure of the ECB’s policy. It highlights the failure of governments’ economic policies.

Governments should implement growth-oriented reforms lowering taxes and attracting capital. Many will not. Most will likely decide, again, that they need to spend more. Fail, repeat.