(published in Cotizalia on November 12th)This past week I had meetings with investors and funds in Geneva and Zurich and the mood remains sombre.

Europe is increasingly giving worse news, the Super Committee is getting nowhere and investors see the market collapse only to recover a fraction of what it lost.The United States and Europe are in recession. The current uncertainty lies only in the magnitude of such recession. In this environment a group of friends from hedge funds and investment houses have chosen the stocks and assets that, from their point of view, can win in a recession. It is an exercise we did for the first time with a group of 35 professionals in 2001 and repeated in 2008 with very positive and interesting results. Of course, the following list is just an illustrative sample of what a group of experts think.The initial premise of the survey assumes a stagnant economy and rising inflation on the side of commodities because of the monetarist policies of the governments of the OECD. In this environment, we look for companies that have chosen a precise and inflexible approach to increase margins, competitive position and high cash flow, lower costs and greater return on capital. Well, here are the favorites:

The favorites (by number of votes):

Philip Morris . The business is a cash machine, with a captive market and growing in emerging countries and a dividend paid entirely from free cash, with a Return on Equity (ROE) of 242%.

McDonald’s . The fast food giant sales increased by 5-7% in all its markets, opening a restaurant every two days in China with an aim to reach a day in 2012. A business that sells in hard times more units of higher-margin product (cheapest burgers), with a return on equity (ROE) of 40%.

Campbell: Campbell Soups generate strong growth with good quality products and very low price. A Return on equity (ROE) of 76% and almost no debt.

Walmart: A favorite of the last recession, impressive handling of costs and low prices. Generates a return on assets that increased in harsh environments and a return on equity of 22% with $10.6 billion in cash.

McKesson. Solid healthcare favourite, fully oriented to improving profit margins. A 23% Return on Assets and $3.200 billion of cash.

Exxon, accumulating $9 billion in cash, with a return on capital employed of 25% at $70/bbl (compared with 12% of its competitors) and totally inflexible when protecting investors against attacks from governments, which has been especially evident during the Obama administration. Wrongly seen as a value trap by some, this is by far the safest bet in energy for a recession. in Europe, Shell is the favourite due to its outstanding cash-on-cash-returns and discipline in capex, added to low exposure to “value destructing” diversification businesses.

KBR, Halliburton’s former subsidiary generated a lot of criticism from the press for its contracts in Iraq and its military support division. All this is behind us and today it’s a machine of positive returns (19% in a negative environment) and winning contracts despite the economic difficulties of many countries. No debt.

Seadrill: 11% dividend yield and winning contracts at day-rates that come 15-17% above competitors. A safe bet on the tightening deepwater drilling market.

G4S. The British company offers security services, with a return on equity of 20% and good dividend, the business has gotten only better in recent years.

The Spanish:

With the highest number of votes, the only stock in the Top 25 is Inditex . It has better return on capital than Walmart, attractive growth and €3 billion in cash, a business model that has nothing to envy even from Exxon.

Finally, most opt for ETFs in gold, coal and platinum.

The Shorts of this anti-recession portfolio are dominated by the CAC Index (France) for its excessive debt, high weight of problematic banks, strong state intervention in their businesses and risk of infection of the Euro debt crisis. This is followed by environmental services companies (Veolia, etc..) still seeing deterioration in returns, lost margins and increasing debt, plus the European telecommunications companies (Telecom Italia, Deutsche Telecom, France Telecom) that see their returns fall to levels dangerously close to cost of capital, and the equipment sector in renewable energy (solar and wind turbines, Vestas, Gamesa, Solarworld…), which are seeing disappearing subsidies worldwide while the over-capacity eats away returns, working capital requirements increase and growth collapses.

From my point of view, this exercise in choosing the companies that win in a recessionary environment also helps to understand how important it is to have global leaders that focus their strategy to generate better returns on capital employed, not creating overcapacity and that forget the dream of “improving cost of capital” by increasing debt.

Surprisingly the main difference between the stocks mentioned and their European competitors lies both in cash as in returns and margins. And that is fundamentally a strategic and cultural difference regarding the importance of margins and returns, as traditionally Europeans favour “growth for growth sake.”

Hopefully the macroeconomic scenario is different and that everyone who voted is wrong, but I also hope that our companies learn to deal with a recessionary environment, and not only look elsewhere or expect to be rescued.

Note: Daniel Lacalle can invest in the companies mentioned in the blog, the opinions reflected here are personal and not professional recommendations. The above list comes from a survey, and is not a personal recommendation to buy or sell.

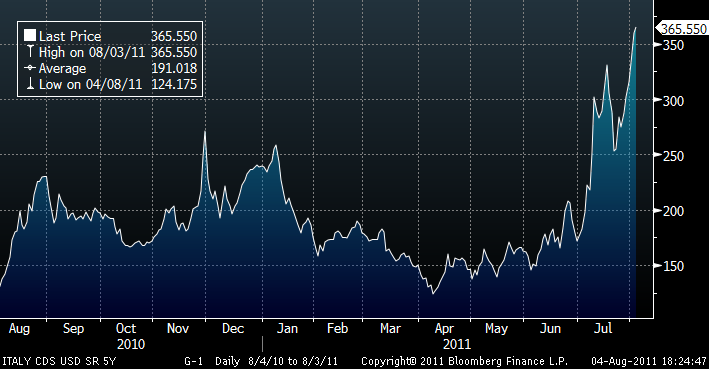

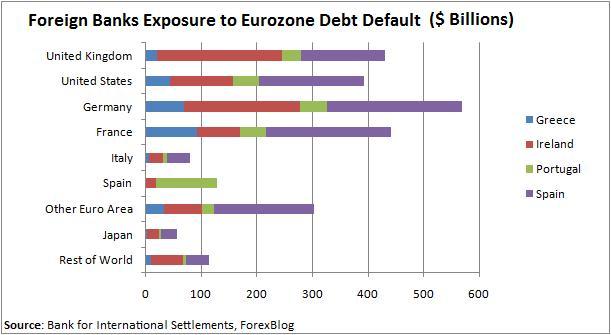

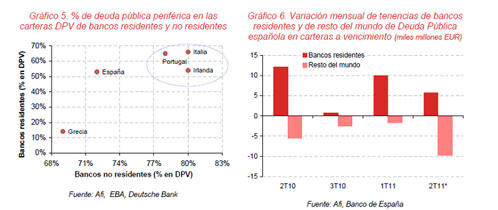

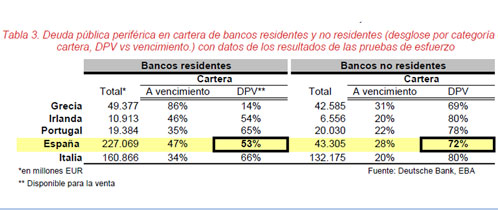

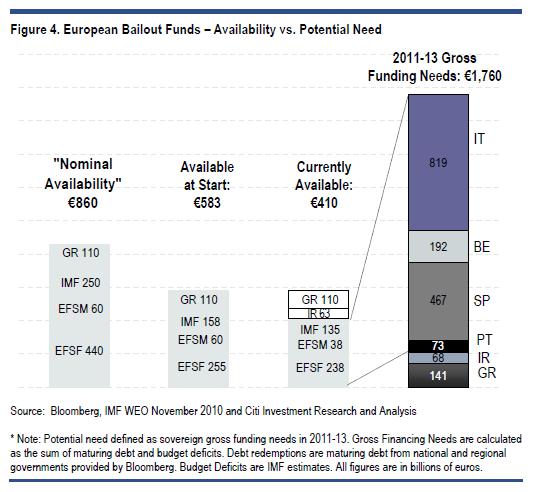

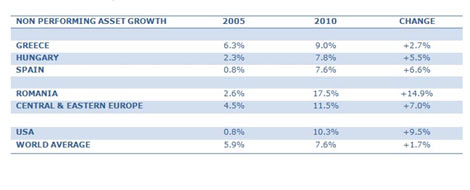

If 100% of Societe Generale’s “core capital” is sovereign debt and for any reason there was a new State problem of liquidity, it would have an immediate impact on the real economy (“shrink lending”) and the financing of French companies. In Italy, UniCredit has 121%, in Intesa 121% in Spain between 76% and 120% … and that’s assuming that all urgent refinancing needs are covered. European states have in excess of €250 billion short to medium term maturities.

If 100% of Societe Generale’s “core capital” is sovereign debt and for any reason there was a new State problem of liquidity, it would have an immediate impact on the real economy (“shrink lending”) and the financing of French companies. In Italy, UniCredit has 121%, in Intesa 121% in Spain between 76% and 120% … and that’s assuming that all urgent refinancing needs are covered. European states have in excess of €250 billion short to medium term maturities.