Integrated oil companies don’t create value for shareholders. This is the unanimous cry of investors.

The conglomerate discount at which the sector trades has now reached record levels (between 20 and 40%) and quarter after quarter investors see that the supposed benefits or synergies of agglomerating refining, exploration and production, gas and electricity and various renewable adventures are seen nowhere in the returns and certainly not in the share price.Of course, we continue to see slides where companies applaud themselves for being “large”. Large conglomerates of many capital intensive businesses with poor profitability. Because today we do not see the benefits or improved competitive position with respect to independents either in growth or relationships with producing countries. Big Is Not Beautiful .

“Long term, Lacalle, these are long-term investments.” I hear. Well, long term investors have not been rewarded at all. The European integrated oils (red line on the chart above) since 1998 have performed quite poorly while oil rose from $14 to $114/bbl. Meanwhile, independent explorers rose c300% (12% annually) in the U.S. (white line) and 500% (20% annually) in the UK. Furthermore, the oil services companies (green line) rose 155% (7% annually). For reference, I remind of my posts on oilfield services and independent explorers.

With oil prices increasing almost tenfold, the integrated European sector average performance since the end of the mega-mergers, 1998, has been a paltry 3.8% annually. Considering they have paid a dividend yield in that period of between 3% and 6% and assuming that such dividends were reinvested, the real stock market performance has been almost equal to inflation. Destruction of value of spectacular size.

But it’s even more impressive to see how terribly the integrated Europeans have performed (+3.8% annually in dollars) compared to the Americans (+7.6% pa) since the days of mega-mergers.The reason, sad to say, is that the Europeans have generated an average 12-16% ROCE due to the “diversification” into many low-return businesses, while Americans were generating a 18-23% ROCE. In Europe, poor refining investments (remember “the golden age of refining” bet?) and adventures out of the sector from renewables to power and healthcare, telecoms and nuclear, have “eaten” the profits of exploration and production. Investing in refining in Europe is a donation, not a business.

It’s a shame, but many of the European oil majors are semi-state political vehicles where the alignment of interests between shareholders and managers is very low. As an example, using data from annual reports, we find that European managers have virtually no shares in their companies (less than 0.01% of capital), compared to 6% on average in the U.S., apart from the giants Chevron Exxon or Conoco (between 1% and 1.2% of capital). People tend to work harder if their own money is at stake, and if a CEO has more desire to become a minister than to see shares go up, his actions will lead to his principal goal.

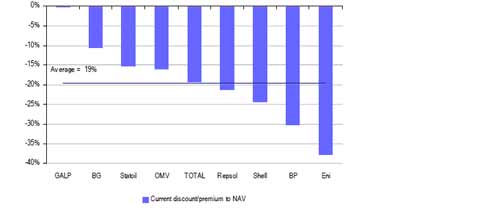

No wonder, then, that ROCE driven companies outperform. Exxon just trades at a 4% discount compared to the sum of the parts of its businesses, while Chevron trades at a premium of 4%. On average, the listed American integrateds, according to UBS, trade at a discount of 5-8% while ENI (Italy, semi-state) trades at a 38% discount, OMV (Austria, semi-state) at 16%, Total (France, private but with strong public ties) at 22%, or BP (private but a “flagship company”) at 30%. Repsol, which emerged from the “Argentina trip to hell”, used part of the philosophy of Marathon (either by choice or necessity or shareholder pressure) has cut its discount from 40% to 20%. But it still has much to do to be remotely similar to Murphy or Marathon and it is important to remember that maintaining control positions in listed subsidiaries does not help because the conglomerate discount remains.(source: UBS)

No wonder, then, that ROCE driven companies outperform. Exxon just trades at a 4% discount compared to the sum of the parts of its businesses, while Chevron trades at a premium of 4%. On average, the listed American integrateds, according to UBS, trade at a discount of 5-8% while ENI (Italy, semi-state) trades at a 38% discount, OMV (Austria, semi-state) at 16%, Total (France, private but with strong public ties) at 22%, or BP (private but a “flagship company”) at 30%. Repsol, which emerged from the “Argentina trip to hell”, used part of the philosophy of Marathon (either by choice or necessity or shareholder pressure) has cut its discount from 40% to 20%. But it still has much to do to be remotely similar to Murphy or Marathon and it is important to remember that maintaining control positions in listed subsidiaries does not help because the conglomerate discount remains.(source: UBS)

We recently explained why the integrated sector does not work in the stock market , but what would happen if they broke into parts?. Let us focus on the possibilities of a break-up to create value:

1) Not all have to. As we have seen, American integrated trade at a small discount or a premium to their sum-of-the-parts, thanks to the ongoing evaluation of their business portfolio, and having no mercy when it comes to divest in areas of low profitability .

2) Not all can do it . In order to do a successful break-up companies need to start with a powerful exploration business, with high growth that would trade at a strong premium and a very strong refining and marketing business with strong cash flow and good EV/complexity and margins so that investors value them. Marathon and Murphy are companies that have exploration and production businesses that can trade at higher multiples, but also very successful in refining so it is easy to separate them.

In the European case it is more difficult because usually companies “limp” in one division or another. They are also companies with more “surprise invested capital” (a lot of hidden diversification with low returns) and thus this could lead to a separation at very low multiples. For example, despite having a world-class exploration and production business, Total’s refining + marketing + renewables, which has generated losses in France since 2001 as the CFO acknowledges, could not be separated. If Total, for example, could not close the refinery in Dunkirk, losing millions a month, could Repsol sell its inefficient refineries given the same pressure from local governments?

BP, for example, also has a powerful exploratory heart, but very low growth (Thunderhorse, etc) and average exploration success, and is still trying to sort out its disastrous Russian adventure (TNK, 20% of its reserves), sell their underperforming European refining and reduce exposure to its renewable business at a time where renewables are falling in valuation every day. If it separated its activities in three, as some propose, these would very likely trade at sub-peer multiples as well.

There are also many pressures and core-shareholder policies that prevent companies from selling non-strategic assets. From ENI with its subsidiary Snam ReteGas and Galp, to Repsol and Gas Natural, which at some point traded at €40/share when it was a possible candidate to be sold, yet now trades at €14/share after a massive acquisition and a capital increase.

Furthermore, disposing of those assets would probably show to investors that the alleged “high growth” E&P division is probably not going to trade at the multiples of an independent explorer given the fact that, at the core, in most integrated oil companies, the exploration success ratio is well below that of independent companies, the reserve replacement is lower and they are not takeover candidates or sellers of assets, just aggregation vehicles.

Separation has only proven to create value for all stakeholders (shareholders, industry, country) when the parts are true growth and value, as the model of BG and Centrica showed, which delivered two strong national companies without massive conglomerate issues, lean operations, higher ROCE and clear market valuations. This made them also bigger and better companies.

3) Not all should. One should ask – sell and separated to do what? Sometimes you have to be careful what you wish for. When some of these companies are separated, the excess cash is often used to make acquisitions, and given the examples of the past, it is sometimes better to stay with the devil you know.

Example: If ENI dispose of Snam it would lose €2.5 billion in operating profit.As an industrial and semi-state owned company, it would seek to acquire something that would replace that figure. And would probably be more expensive than the asset sold. Unless those gains are reinvested in buying back shares, pay dividends or make one acquisition of very obvious high value, the benefit may be non-existent. So the only way to create value is to forget trying to reinvent the wheel and focus their efforts on growth in exploration, an area where their returns and competitive advantage are obvious.

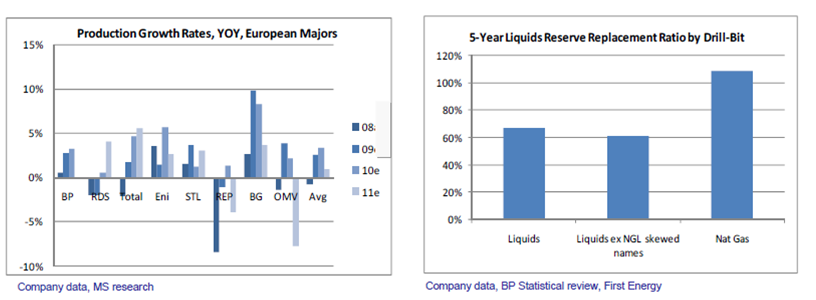

The illusion of value in Euromajors’ E&P businesses is another contention issue. If we look at European majors’ E&P business from the perspective of an independent upstream company, here is what we find: No real organic reserve replacement (most of it is acquired), sub-standard growth (1-2% pa at best), very exposed to OPEC, gas and non-conventional resources, exploration success below-E&P standards in past five years at less than 35% (versus E&Ps at 56%), low ROCE (15-17%), bureaucratic and slow management decisions. But most important, a major’s E&P business, even if restored to industry standards, is not for sale as they are asset aggregators, so it would never be valued on a NAV basis like other E&Ps. See the example of Statoil, which is now a pure play E&P, has no conglomerate problems and still trades at 16% discount to sector.

The only upside from integration is size and scale. By staying combined and being huge $100bn+ companies, the majors force the market to value them on P/E, and dividend yield rather than being subjected to the scrutiny of production growth, ROCE, reserve replacement etc and EV/complexity adjusted barrel, margin, cash-flow etc that smaller pure play peers are subjected to in upstream and refining.

The weakness in the theory of break-up value as a strategy is that by splitting up they subject themselves to a comparison of their individual businesses vs peers, and the comparison is bound to be poor on growth, on exploration upside, cash flow and ROCE. So it seems that majors are happy to complain about their share price, but prefer to continue to mask poor strategic and operating performance vs independents by staying “too big to ignore”.Ultimately, as we said a year ago, be wary of promises of value based on estimates of sum-of-the-parts. Because it ends as a text-book case of “value trap.” And let’s welcome focused strategies. At the end of the day an oil is not an NGO, it’s a “capital allocator” which should review its portfolio of businesses each year and cut off mercilessly the areas of low profitability … As Shell has begun to do since Peter Voser beame CEO. And forget the “long-term value” mirage. As Exxon says, there is no long-term strategy that cannot be monitored from quarter to quarter. Size does not matter unless it creates value

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304537904577277440911481180.html