This article was published in El Confidencial on October 12th 2012

“EU wins the Nobel Prize for pillaging its People with debt and bailouts.” Keith McCullough

“Doing a rescue right bank is more costly, not less, which is why political leaders prefer to zombify rather than clean up their banking systems”. Yves Smith

This week I had a meeting with readers of El Confidencial and commented that the global sovereign debt bubble is already bursting, a bubble that is closely linked to reckless public spending financed with a bloated banking sector that is now rescued with public money and the creation of bad banks.

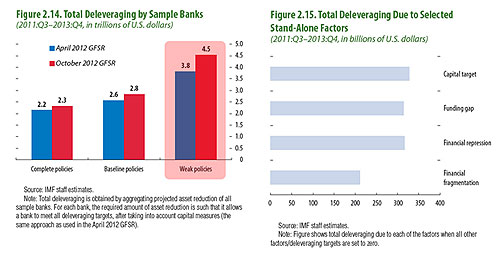

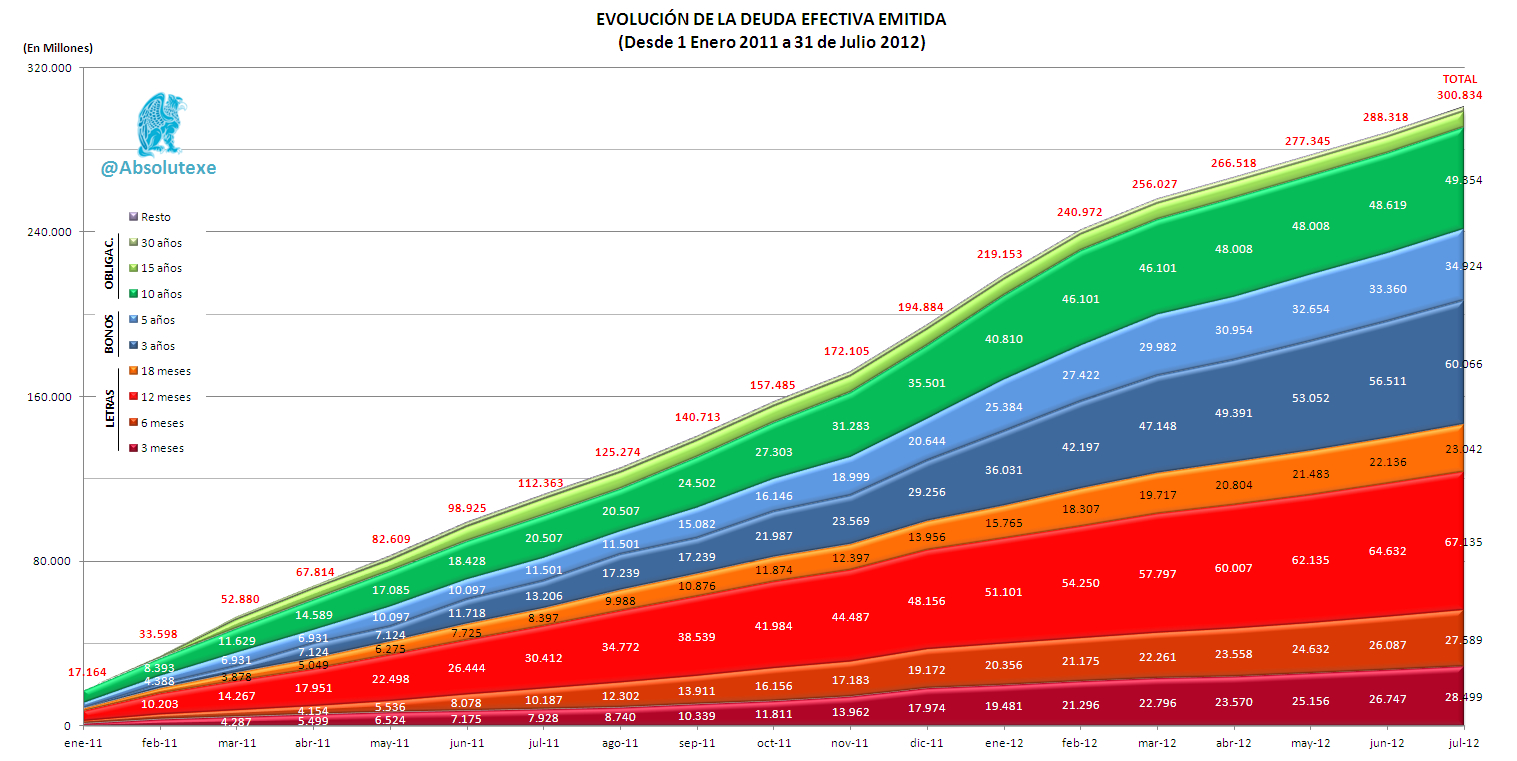

States fail to grasp the problem of shrinking assets and deleveraging. The available capital to invest in sovereign debt has been shrinking every year by 3.5% globally since 2007, while government issuances and government-guaranteed bank bailouts have increased by 8% pa. In Spain we are six years behind most countries in the clean-up process, so the impact is likely to be larger and in a shorter period of time.

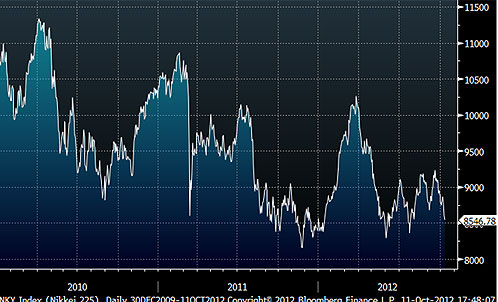

When the regional governments and the EU member states came to London to try to pitch their bond issuances they always told us that their banks were world-class models of management and risk control, and that all the regions individually had less debt than Japan. Now we run the risk of seeing the two lost decades of Japan by copying their policy. We want to be a “Japan without Toyota”. And Japan has its own serious problems.

The bad bank and the financial system bailout, like Japan

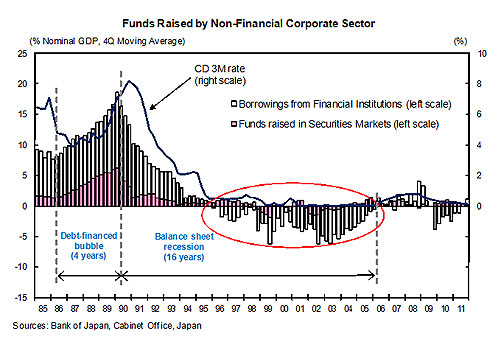

Japan carried out bailout after bailout from 1995 to 2005 and in 2008 under the same premise that we have now in Europe, a premise that has already failed in Ireland. “Everything goes up in the long term”. The long term will solve everything, valuations are “attractive” and creating a bad bank will improve credit to the real economy. Well, no.

Doubts about the bad bank in Spain are not coming from uncertainty, but from the certainty that it hasn’t worked in the past. Investors do not want to accept the valuations of loans and reject investing in the bad bank. The press calls them “vulture funds”. A failed bank that cannot sell its assets or clean its loans meets a government without money and both demand that international investors buy toxic assets at an agreed price between the first two so that it doesn’t look bad in front of creditors and voters… Yet the one the press calls “vulture” is the investor.

From the lost decade … to the two lost decades

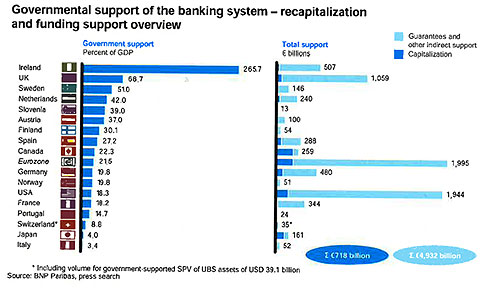

Sorry for the poor quality of the chart below, but it shows the following. The OECD has spent more than 4.9 trillion euros to rescue banks from the crisis. That’s 4 times the GDP of Spain. Except in very specific cases, like the United States and little else, virtually nothing of that “aid” has been recovered. Why do they do it?.

Because it is feared that the fall of banks is more harmful than keeping them zombie and wait until the crisis ends and valuations rise. But it doesn’t work. Toxic is toxic now and in ten years. And governments never think of “working capital” and “interest accrual” as a problem while the “long term” arrives.

Five years ago a French banker told me that “no one dares to analyse let alone reject a loan to the government”. It is extremely difficult to clean the system from a way of doing politics, of building useless infrastructure, housing bubbles and interventionism in what is euphemistically called “growth policies”.

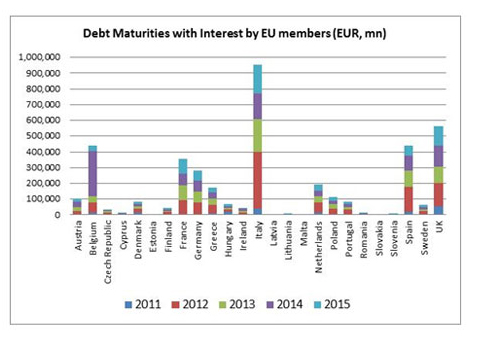

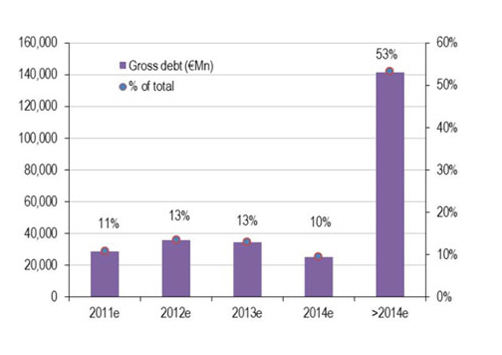

The problem of bad banks is that past experiences do not help, and even if we repeat again and again that the crisis was of US origin, the problem is Europe. Let me show you a few figures to illustrate the enormous problem of the European banking system:

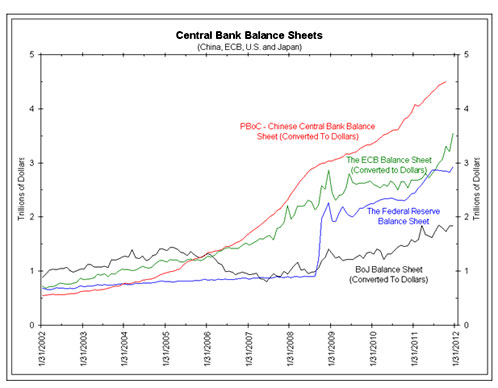

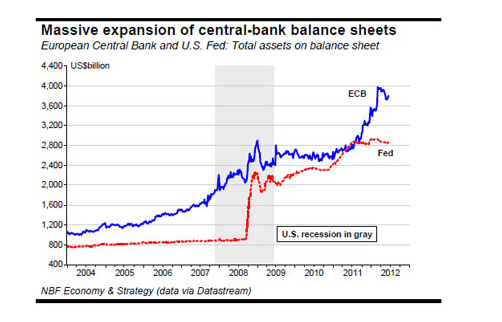

Half of the world’s largest banks are in the European Union. 56% of European banks have political or public control. In 2010, U.S. banks had a balance sheet of 8.6 trillion (80% of GDP). In the European Union, banks’ balance sheets exceeded 43 billion euros (350% of GDP). According to the IMF, European banks have to divest up to 4.5 trillion euros. Will credit flow? No.

At this point it is doubtful that the discount at which the Spanish bad bank will buy toxic loans is adequate. In fact, what many perceive is that the problem of the loan portfolio is not of “non-performance” but absolute insolvency, especially in land. Another risk is that the bad bank may have only 10% of capitalization making it a giant leveraged bet on the rebirth of the housing bubble. When the government says that the bad bank will not cost taxpayers a cent it is just saying that they expect -pray- that asset prices will rise. Meanwhile citizens have less disposable income due to confiscatory tax policies. It is difficult to see a recovery in housing with wage and disposable income deflation, just like in Japan in the 90s.

Last week the Irish Minister Joan Burton commented that the Irish bad bank, NAMA, will probably lose 15 billion euros of the 32 billion paid for the “toxic loans” acquired by the taxpayer at a “bargain” 58%” discount.

The solution, in my view, is the “bail-in” of banks. Liquidate the problematic entities with bondholders and shareholders taking losses. Europe cannot have a banking system that is five times larger than the American. A bail-in would separate the good from the bad banks and address the problem of public debt paid with taxes and spent on bailouts.

Sinking the economy the Samurai way

All I read over and over is that Europe needs “social contract and growth policies”, which means more welfare state, more government planned infrastructure and not worrying about deficits… Like Japan. But Europe is not Japan. And even if it were, it does not work. Europe cannot emulate the race of debt and public spending made by Japan because it would be committing hara-kiri .

Japan is the dream of a European interventionist government or a minister of Civil Works: Expenditures on useless infrastructure, endless civil works and a pyramidal welfare state increasingly at risk of insolvency due to its declining population.

Japan spends 60% more than its revenues, has a deficit of nearly 10% of GDP, net debt – deducting some government assets – of 135% of GDP. In 2013 Japan has to issue debt equal to 60% of its GDP (source The Atlantic).

Half of the Japanese budget is wasted on debt interest expense and pensions. Does this sound familiar?. With an aging population in which the pyramidal structure of the welfare state and public spending were unchanged, Japan is living on borrowed time and its citizens contribute their savings to maintain a public debt that is not secured by assets. Does this sound even more familiar?

In addition, 95% of Japanese debt is held by local investors. In Spain, Portugal and Italy it is close to 65-70%. This seems to be the goal of the EU leaders for peripheral countries. Local buyout of public debt. But the Japanese save and their companies are world leaders in exports. Japan repatriates currencies. Europe, especially Spain, consumes currencies.

And yet, the “Japanese” solution to the recession is what some seem to repeat over and over again, eternal social guarantees and public spending, even if this has only led to a crisis of the “two lost decades” and an unaffordable debt.

The fans of the “policies of growth” want Japan without Toyota… And it does not work.

Japan has modern industries and technology, moderate unemployment and a powerful industry. It also has a large savings ratio. Despite this and being a world superpower, Japan is heading towards the largest debt crisis after another decade of reckless spending. Because it depends on the savings of an ageing population whose disposable income continues to decrease. The crisis could be the next financial tsunami, because the pyramid scheme of debt financed by domestic savings is being consumed.

Those in Europe that demand the European Central Bank to behave like the Bank of Japan, fuelling the public debt bubble, and that want the state to undertake “guaranteed welfare and growth policies” are betting on being Japan without its private savings or industries. It’s suicidal.

The solution is not to borrow against our grandchildren building more useless airports and trains in a Ponzi scheme to subsidize the short-term placebo effect of ephemeral subsidized employment. Zombi banks must be liquidated, without cost to anyone but shareholders and creditors. We need real market economy.

The solution hurts because there are no miracles. De-leveraging will take a long time, and in the meantime we must revitalize the European economy by attracting private investment. But that does not provide votes or photo opportunities inaugurating useless bridges. We want Japan, but without Toyota. Someone will pay.