(This article was published in Spanish in Cotizalia on February 4th 2009)

The results of Shell, Chevron and BP have shown once again the extremely serious problem plaguing the oil industry: refineries lose more money every quarter and completely offset the positive results of exploration and production or gas trading. In fact, the refining sector in the OECD has generated returns of c3% below the cost of capital since 2003. Tony Heyward, CEO of BP, Europe’s largest oil company, was forced to acknowledge at the presentation of Tuesday’s results what has been a concern for the investment community for years.”Refining margins shall remain depressed for the foreseeable future.”

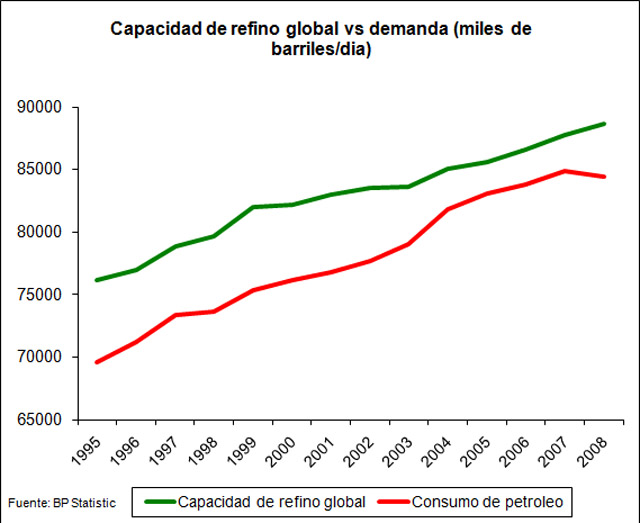

Indeed, the world finds itself with excess refining capacity of more than four million barrels a day. In addition, between China, India, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Korea there are planned refinery projects for more than 8 million barrels a day, many of them justified for purely political reasons. Even if half of them were canceled, the overcapacity will remain for at least 10 years. Meanwhile, Europe and the United States see the value of refining assets plummet every day, well below replacement cost, and no buyers. ENI has been unable to sell its refinery in Livorno and Total is not only unable sell its Flanders plant, but due to government intervention they are forced to keep it operating despite the fact that Total loses around € 100 million per month in the refining area.

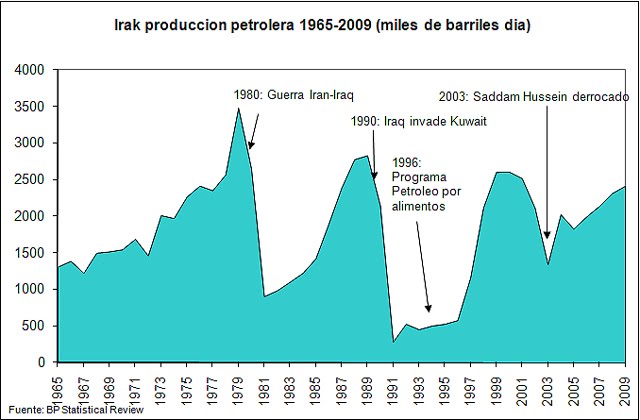

The situation is desperate, even for companies like these, who do not have debt problems. As you can imagine, much of the refinery projects were built with the frightening words “security of supply” and “strategic” as a justification, regardless of the volatility, low return and very high investment requirements. We have not learned from the debacle of 1981-86, which led to curtail refinery capacity in the OECD by 20%.

In the past, integrated oil companies wanted to sell the message of their refining activity as an alternative to volatile oil prices, but it has proven to be a source of massive capex requirements and destruction of market value for the sector.

At the end of the day, a refinery creates value only if it can extract superior returns by using cheap and low quality oil (heavy) to produce high priced gasoline and products. Expensive oil, with the differential between heavy and light crude at a 10 year low, added to excessive costs, declining demand and efficiency improvements have led refining margins to plummet to $ 3.8/barrel on average, the lowest levels of the past 15 years. And this even when refineries are running at an average of 80% capacity. But the differentiating factor is that excess capacity far exceeds the most optimistic expectation of improving demand.

Some might say that this is scaremongering, that refining is a cyclical business and that when demand recovers everything will be fine (amazing to see how many times one hears this lately). I disagree. None of these large oil companies look to their activities on a short-term basis, and yet all of them seek to reduce refining capacity, the sooner the better. Apart from ENI and Total, Royal Dutch Shell aims to reduce its capacity by 15%, Valero has closed its plant to 200,000 bbl/ day in Delaware, BP wants to reduce its capacity by 14%, Chevron also … In summary, the 10% fall of demand in 2009, that all oil companies see as structural, not cyclical, will lead to the closure of at least 3.4 million barrels per day, up to 18% of the entire European capacity, between 2010 and 2020. And still capacity will be more than adequate.

Spain has refineries to bore, nine, with a capacity of over 1.1 million barrels a day. Within the complicated picture of the sector, some are reasonably profitable. For this reason, they could be sold without any problem at a price close to $1 billion per plant. The opportunity to raise cash and reduce investments has to be taken. But beware of waiting around for the return of the “golden age of refining” which may be decades away … or not return.