By Gustavo Teruel, CFA For CFA Institute. Nov, 2014

What’s Really Behind the Plunge in Oil Prices?

In early 2013, we interviewed Daniel Lacalle, a London-based energy analyst. Lacalle has also been active in the media in the last few years, airing his views about the markets and the economy on his website and for El Confidencial. He has been a regular guest on most of the major financial media outlets. Since our previous interview, Lacalle has published three books in Spanish and one in English (a translation and update of his first work Life in the Financial Markets) and will publish his second book in English, The Energy World Is Flat, in the next week.

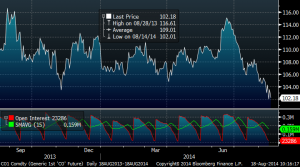

Given the latest developments in the price of oil and their implications for the broader market, we at Enterprising Investor thought it was time for a second round with Lacalle. We spoke with him last month, in the midst of the plunge in oil prices — a trend that has only continued in recent weeks, rendering some of the figures mentioned out of date.

Gustavo Teruel, CFA: Daniel, you have been quite bearish about the fundamentals driving the oil price in the long term, I guess you must be feeling vindicated these days?

Daniel Lacalle: Evidence was mounting and very few wanted to acknowledge it. While the “peak oil” conspiracy theory continued to be proven wrong, its message remained in the public consciousness, and the oversupply in the oil market grew. I received a lot of criticism, particularly about the resilience and strength of the non-OPEC supply growth as well as the slowdown in Chinese demand. Today, no one questions it — I hope.

The last time you wrote about the moves in the price of oil was 30 November 2014. Do you think there has been a downward overshooting?

It is not overshooting. Oil prices have been rising on the back of a pro-cyclical cost curve. That is, service costs and development costs tend to rise as oil prices go up and investments increase well above the market’s needs. The industry has gone from underspending in the late 1990s to overspending — close to $1 trillion a year — on the back of an elusive growth of demand that has been proven incorrect. Efficiency and a less industrial model have proven that the correlation between real GDP growth and energy demand is broken. We do more with less, and the unit of energy needed to create a unit of GDP is lower today than 30 years ago. Now we find that many of those investments made in the 2004–2013 period have created overcapacity in the system.

What happens is that oil prices, when OPEC refuses to be the balancer of the market, test the marginal cost of production — and costs fall. High-spec sixth-generation rigs, pressure pumping, seismic, completion — all these costs have fallen between 20% and 45% in the space of two months as overcapacity becomes evident and excess capex [capital expenditure] is revised.

OPEC’s decision not to balance the market through cuts makes total sense. It was not OPEC who increased production well above demand in the first place, and they are also the lowest marginal cost of the curve. Why should OPEC countries cut production to let non-OPEC countries grow even further and erode their market share year by year?

Conventional wisdom credits the conspiracy theory that says the decisions made by Saudi Arabia with regard to output have the sole purpose of hindering Russia, for geopolitical reasons, or, at a minimum, the least-efficient producers. Do you believe that is the case or do you think the cartel’s influence goes only so far?

I think those conspiracy theories tend to flood the energy market because they make the analysis look simple. And by accepting the conspiracy, it stops us from really understanding the issues. There is no desire to harm anyone. Saudi Arabia does not need to balance the market for non-OPEC countries to grow their production when the kingdom’s production costs are the lowest. It is like thinking that an efficient and low-cost producer has to reduce output to let the higher-cost producers thrive. Saudi Arabia and the rest of OPEC are simply showing the world and their clients that they are the low-cost, efficient producers and that they can sustain a period of oversupply. It is up to the other producers to see whether they can be more efficient or not. It is not “harming Russia.” Many countries, including Saudi Arabia, lose excess oil revenues, but they will adapt. Saudi Arabia loses $100 billion of revenues from these oil prices, but like many OPEC countries, they have no debt, strong currency reserves, and a low cost base.

Saudi Arabia is defending its market share and proving it is low cost. But more importantly, OPEC knows that cutting would be damaging for them and ineffective. The world has about 2.5 million barrels per day of excess supply. Would OPEC cut almost 10% of its production to keep prices higher and support the rise of non-OPEC production, which is growing around 3% per annum? This makes no sense. A cut would only extend the overcapacity and just erode OPEC’s market share.

Some market strategists, pointing to historical precedent, are now saying that the price of oil is going to remain low for years. Don´t you think we have reached a point in oil prices where market dynamics — the rise in fuel consumption, the shutdown of projects, the cuts in capital expenditures — can only add upward pressures?

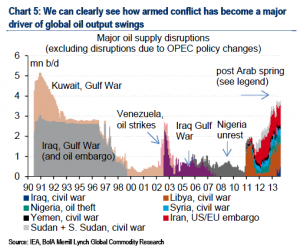

Oil can go lower. Maybe to $50/bbl [barrel] [Editor’s note: this interview was conducted before oil fell below $50/bbl in early January.] Al-Naimi [the Saudi Arabian Minister of Petroleum and Mineral Resources] mentioned it could go to $40 or even $20. It was only eight years ago when it was at $45–$50/bbl in real terms (we always speak of oil in nominal terms, which infuriates me). Oil is at 1978 prices in real terms today — that is, counting the impact of inflation. Neither demand nor supply dynamics have tightened the market dramatically. Excess capacity has only grown from 1–1.5 mbpd [million barrels per day] to about 2.5–3 mbpd. I do not know if there will be spikes due to one-off events, but I know that oil is at $60/bbl today, despite the fact that Libya’s exports have been slashed [in December] by 400,000 bpd and that non-OPEC growth estimates have been revised down by around 700,000 bpd. This tells you how well supplied the market is. Despite ISIL [Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant] and Iraq, Libya, the Russian crisis, and Brazil’s scandal — all of which could affect production — the supply-demand balance remains ample. One thing is for sure: the period of disinflation in oil prices can last longer than what many predict.

It seems that the smart money is entering the industry. They claim that the rationale of this move is that there has been indiscriminate selling of asset classes and sectors of the market due to the way exchange-traded funds (ETFs) work, which has left the market rife with opportunity. I guess the second point of the rationale is that they believe the stickiness of capex in the industry, hedging, and the upward trend of prices from this point will keep the companies they are investing in afloat. Do you share that view?

[Laughing] If the market moves against your thesis, blame the speculators, not the wrong thesis. I love it. Again, it is simplistic — and wrong. The poor speculators — they are to blame when prices go up and when they go down as well [laughs]. According to data from the CFTC [US Commodity Futures Trading Commission], net length in oil increased [in] December and oil fell. ETFs and speculators do not make the price. They buy financial products referenced to the physical price, not the opposite. CFTC data show that speculators are still net long oil futures by 300,000 contracts, a very large margin compared to a few years ago.

Anyway, we have some investors in the market who want to believe this is a temporary glitch and want oil to go higher to justify investments in stocks and debt. That is fine, but is nothing more than a desire. I remember when natural gas prices collapsed from $12/mmbtu [million British thermal units] to $6/mmbtu, many said the same — and they fell further, to $3.6/mmbtu [Henry Hub]. This is because their view of the fundamentals is flawed due to a number of misconceptions about the industry:

– Forgetting that spare capacity becomes a sunk cost and many producers just run for cash, not for 10% or 20% IRRs. Remember refining — a business that has been delivering below the cost of capital returns for many years, or seismic, or shipping.

– Ignoring efficiency and substitution. Just by improving light-duty vehicle motors in the United States from 24 to 34 miles per gallon reduces oil demand by 4 mbpd, almost four years of growth. Just a 6% penetration of hybrids in the United Kingdom and United States would reduce demand by 3.5 mbpd.

– The industry is not self-adjusting, as many want to believe, but pro-cyclical. As such, megacap major oil companies tend to acquire low-hanging fruit not to tighten the market, but to grow and expand. The large acquisitions in shale gas in 2009–2013 did not reduce oversupply in the United States — they prolonged it. The industry becomes more efficient and adapts to lower prices, it doesn’t shrink to tighten.

To summarize, be careful about buying ex-growth sectors on the promise of internal adjustment. As in utilities, coal, gold, or refining, it can be a deadly mistake.

How do you see the situation with the vast amounts of high-yield debt used to fund shale oil ventures? Do you think, as some pundits argue, that there will be a wave of defaults that could trigger a severe downturn in the United States, as happened with the burst of the housing bubble?

This is ridiculous. They talk about the shale bubble when energy is less than 5% of the commercial loan book of banks, and less than 14% of the entire high-yield spectrum. And, they compare that to housing, which was multiple times those figures!

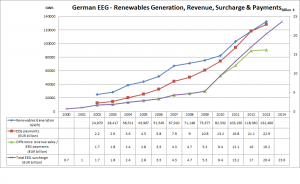

These people see shale, with the high end at 2.5-times net debt to EBITDA, as a bubble but do not see renewables, which have 4.5-times to 6-times EBITDA debt, as a bubble?

Just think of the following figure: if there were 13% NPLs [non-performing loans] in energy (to use the NPLs of housing from the Spanish banks, for example) in the entire United States, the total figure would be around 0.1% of the banks’ loan book and less than the NPLs in solar of peripheral Europe today!

These fearmongers forget that the oil industry is less indebted today than it was years ago, that 90% of shale production is profitable at $60/bbl, and that out of the hundreds of companies, very few breach their covenants at $60/bbl. They forget the example of shale companies, which successfully navigated the collapse in US gas prices. They forget that the equity market and M&A [merger and acquisition] ramp up with these opportunities. More importantly, they forget that more than 80% of shale production comes from monster-large companies like Exxon, Shell, Statoil, Continental, Anadarko, Occidental, Hess, Devon, Apache — with some of the strongest balance sheets in the world — who have successfully survived low and high prices and many geopolitical crises and events. Will there be some bankruptcies in the small names? Maybe, but those companies and licenses will be acquired by larger, more efficient players.

I find it ironic that the doomsayers focus on shale, when in 2014, with high subsidies and low interest rates, we saw a record number of solar bankruptcies — the list of carcasses between 2009 and 2014 is staggering. But hey, shale is a bubble [laughs].

One final question about the oil industry: Do you foresee consolidation of the industry? Is there a lot of money to be made betting on which companies will be acquired?

There will be consolidation, but before that happens we have to see excess-capex adjusting, dividend cuts, and really cheap opportunities. We are easily one or two years away from M&A. Remember not to buy based on the greater fool theory, and that M&A does not happen on a mass scale. Learn from the shale gas example or the West Africa upstream example. Those who bet on acquisitions found that valuations went much lower before it actually happened. M&A might be at rock-bottom prices, asset driven, or not happen at all at the levels or premiums that investors desire. Buyers will look for scale, quality, and opportunity to improve efficiency.

A quick question about utilities: How do you think all this is going to affect green energy? Is it easy to pick winners and losers among utilities, given a scenario of cheap oil? What characteristics do winners and losers have?

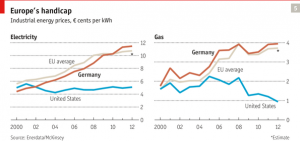

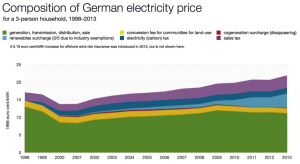

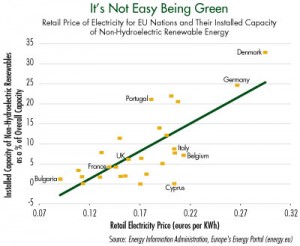

The impact is already evident. Virtually none of the solar and wind projects are competitive at the $100/bbl equivalent, let alone at $60/bbl. Solar PV [photovoltaic] system installation estimates in China have been reduced for 2014, 2015, and 2016 by 2 GW [gigawatts], 2.5 GW, and 3 GW, respectively. Germany will also install 2 GW less than last year. Wind installations are expected to stall globally by 2016. In essence, lower oil prices mean subsidized energy suffers, so it will have to adapt.

Losers bet on cheap debt and on the promise of rising prices or subsidies. Those will inevitably be the low-hanging fruit, as in oil, and will be absorbed.

Winners adapt, become more efficient, learn from the mistakes of the past, and focus on cash-flow generation, a diversified mix, and a good portfolio. The winners will be the diversified, low-leveraged players.

Finally, I would like to ask you about your books. In our previous interview, I asked you whether you thought it was feasible to publish your first book — Nostros, los mercados — in English. You have finally done that, and you have another book in English in the pipeline. I read the Spanish version of Life in the Financial Markets when it was released. Are there many changes in the English version?

Life in the Financial Markets has been updated to reflect the end of QE [quantitative easing], the new era of rising market exuberance after the crisis, the European recovery, the role of the ECB [European Central Bank], and Abenomics. It also covers new elements like bitcoin and high-frequency trading, as well as being more focused on international markets. A reader told me it is almost like a new book — revised, more international, and focused on the issues that matter today.

Your next book, The Energy World Is Flat, is solely about energy. Tell us about the insights this book can offer readers of Enterprising Investor.

I believe it is a detailed guide to the new era of competition between technologies, the battle for market share, the end of oil as transport king, and the war driven by efficiency. The book has been a great success in Spain — it sold two editions in less than two months — and shows, in layman’s terms, the 10 forces that are flattening the energy world and that will generate opportunities in energy globally. It is not a book about oil. It covers natural gas, LNG [liquefied natural gas], biofuels, coal, hybrid and electric vehicles, and renewables at a detailed level, but is oriented to all readers, both experts and non-experts. It also gives advice about investing, avoiding value traps and risks, and opportunities in commodities in the new era after the end of peak oil. I hope you like it.

All posts are the opinion of the author. As such, they should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute or the author’s employer.