In a previous post, we mentioned that stagflation is a risk that central planners are ignoring. However, this risk is not just an isolated challenge focused on economies like Mexico, India or Argentina. Even in countries like Germany and Japan the trend of inflation, particularly in non-replicable goods, is diverging from economic growth. Inflation is picking up, while growth is slowing down.

Central banks continue to pump liquidity to disguise the rising risks to the global economy, but the coronavirus epidemic is showing to investors three important lessons:

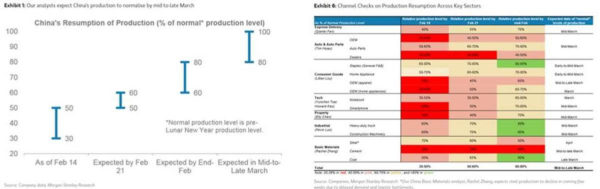

Containment of the epidemic is taking significantly more time than what many market participants estimated. Calls fro a rapid recovery that would not only offset the first-quarter impact but improve it, are disproved.

The impact on supply chains is significantly larger than most analysts expected. China is now 17% of the global economy and provinces that count for 89% of the country’s exports remain in lockdown.

Global excess capacity is a mitigating factor on rising inflation only for replicable and highly competitive goods. There is clearly ample capacity to offset supply chain disruptions in energy commodities, metals, and industrial goods but there are severe problems surfacing in sectors that are very dependent on Chinese supply, particularly auto parts and technology components.

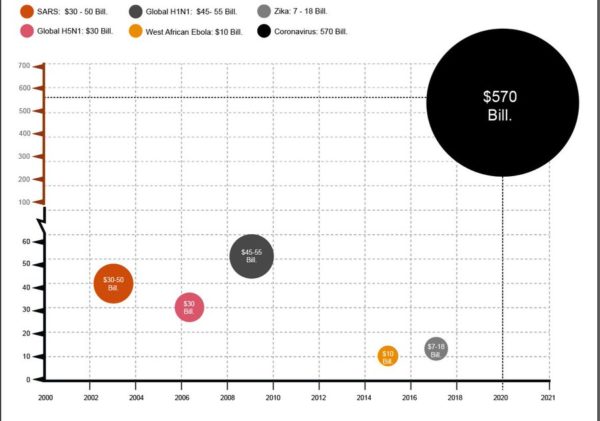

Market participants started to realize last week that the coronavirus effect was not going to be a two-month issue that would be followed by strong growth. In a recent PriceWaterhouse Coopers report, it showed that the global impact could reach at least 0.7% of GDP. This estimate uses Eric Toner´s infected and casualty estimates (John Hopkins Center for Health Security) and the economic impact using McKibbins & Lee methodology (the ones that estimated the SARS impact).

The key factor in this supply chain disruption risk is that while headline inflation may remain weak due to falling commodity prices, the prices of essential goods may continue to rise faster than official inflation and generate more unrest among citizens all over the world.

The coronavirus impact on economies outside of China has not been estimated properly either. If we look at the estimates from large investment banks, for example, they show a surprisingly benign -if not inexistent- impact on the Eurozone and a very modest effect on Latin America. I would beg to differ. The Eurozone’s service economy, that has maintained GDP and PMIs above recession levels, is very exposed to Chinese supply-risk and epidemic issues. Tourism is a clear example, but the overall services economy is significantly more dependent on China, in Germany for example, than current estimates take into account. This could shave off at least 0.2% of GDP growth in the Eurozone in 2020.

One of the bizarre effects of China’s supply chain disruption is that it is showing a positive effect on some economies’ PMIs and GDP estimates because delays in imports add to the external sector contribution to growth (fewer imports adds as a positive to GDP, even if it is due to extraordinary events). This “positive effect”, however, fades rapidly and leads to weaker growth and rising supply issues, which -in turn- generate problems of working capital for many exporters and industrial companies.

If there is anything that has been proven so far is that the estimates of a rapid recovery in February have been disproven by reality and that the process of normalization may take longer than expected. As time passes, the compounding effect on the global economy rises: Fewer dollar revenues for exporting nations, particularly commodity producers, may pose a financial threat as dollar-denominated debt maturities rise, supply-chain disruptions may continue to inflate non-replicable goods’ prices, and economic growth estimates will likely be revised down yet again.

These are risks that we need to consider. Ignoring them just because central banks will continue to pump liquidity and cut rates is irresponsible.

If there is anything that has been proven so far is that some people have suddenly a great interest to scare the populations…

Who wuld profit from this yet another global crisis?

The globalists?

Who had intrest to create this new virus in a lab to destroy China’s economy, growth and credibility?

The US

Who wants to curtain our freedom (of speech, movement and financial) by inventing crisis (LIKE THE 2008 ONe , like the fake ‘refugee” crisis (invasion) and now invent a new crisis to further their sick agenda of a world government?

If all crises are a conspiracy, then the perpetrators would have created another one ages ago.

Not all crises are of conspiratorial origin, however, the facts on the present crisis (Chinese refusal to correct their initial statement of cause of the outbreak, and the media’s refusal to follow up on this cause) lead to the conclusion that for some reason the truth of the matter can not be disclosed to the public.

This in itself is another earmark of conspiracy–hiding the truth.

I conclude there IS a conspiracy, in this case.