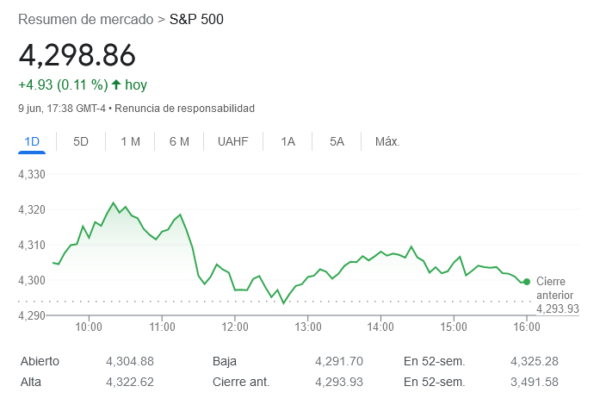

The S&P 500 has risen to a new high and is close to its record level. Complacency seems to be taking hold of market participants because the latest leg up has been driven entirely by multiple expansion.

According to Bloomberg, the Price to Earnings ratio of the S&P 500 has erupted back to 19.2x, almost a 10% increase in valuation with no discernible improvement in earnings or margins. The latest round of revisions shows consensus estimating a -0.28% growth in earnings for this year.

Consumer confidence is back at 2022 lows and the economic surprise index is also weakening. What are investors betting on? Good old quantitative easing to return.

When one looks at the consensus estimates for EPS growth in the S&P 500 it looks like a textbook case of massaging estimates. Expectations of earnings growth have plummeted from +4% to -0.28% in a few months, and energy conglomerates continue to be the darlings of sell-side recommendations despite a slump of 30% in their profit expectations. Meanwhile, consensus is playing its old classic trick: Pump next year estimates. This year EPS growth for the S&P 500 is negative but the following year, analysts expect a robust +10.4% growth and the following year an 8.91% increase. This way, analysts can tell their clients that yes, this year profits will be poor but rising valuations are justified by the strong growth of the next two years… which is likely to be revised down as rapidly as 2023 earnings were.

Massaging consensus estimates is nothing new. According to Bloomberg, the average downgrade of one-year estimates from January to December is 20% in the past decade. Multiple expansion was justified by elevated money supply growth and massive buybacks, which are themselves a second derivative of easy money. In the past, weak earnings growth or declining consensus expectations were tolerated because the monetary laughing gas disguised the accumulation of risk.

Why are investors accepting another period of aggressive multiple expansion in the middle of an alleged monetary policy normalization? You guessed it. Investors now know that central banks will turn on the printing machine at the slightest problem.

Global money supply reached a peak in March 2022 of 105 trillion US dollars according to Bloomberg. It was supposed to fall rapidly to 95 trillion, with central banks unwinding their balance sheet by at least 5 trillion. It has not happened. Global money supply continues above 101 trillion and rose significantly with the banking crisis.

Investors are right to see that central bank policies will remain massively accommodative, and the impact of rate hikes has been limited, providing more an opportunity to increase risk than to reduce it. However, market participants may be too optimistic expecting massive multiple expansion to drive markets. Inflation remains elevated, and being accommodative is significantly different from implementing quantitative easing. Central banks are injecting liquidity in a banking crisis, but they are not driving the valuation bubble further as easily as some expect.

First, fundamentals are not helping. Earnings and margin estimates require further cuts to be aligned with the macroeconomic reality.

Second, inflation may be declining but it is mostly due to the base effect and accumulated consumer prices remain elevated, with core CPI stubbornly higher than what commodities and money supply would dictate. This means that central banks are more likely to surprise with more rate hikes than with the expected cuts into the end of 2023.

Third, investor positioning is falsely bearish. If you read any of the investment bank surveys, it would seem that clients are very cautious and prudent. However, real positioning of institutional funds is extremely concentrated on cyclicals and rising duration bets, net long exposure of Hedge Funds is almost at three-year highs according to HSBC, and the Fear and Greed Index published by CNN is in Greed territory. No, investors are not bearish.

Fourth, and more important: There is a wall of state debt that will flood markets in the next two years. The U.S. alone will likely increase net financing requirements by almost two trillion US dollars, and the eurozone is flooding the market with the gigantic funding of the atrocious Next Generation EU. All that public paper will be refinanced and means less liquidity in markets.

More state debt financed by markets, added to an overly optimistic positioning is a dangerous combination when core inflation remains high.

Markets may remain optimistic for a while, but a correction of the excessively optimistic expectations built in stocks is almost inevitable.