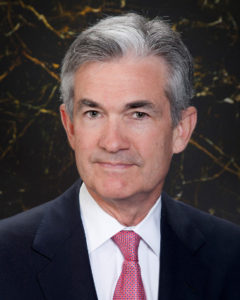

However, the first conference by Jerome Powell as president of the Federal Reserve gave us very positive surprises.

However, the first conference by Jerome Powell as president of the Federal Reserve gave us very positive surprises.

Powell was clearly cautious with long-term estimates, one of the Achilles’ heels of a Federal Reserve that consistently missed its own inflation and growth expectations. His response to a reporter on their predictions for 2020 was perfect. The Fed has to monitor the changes that are taking place, and avoid giving optimistic estimates that only make them lose credibility.

And now, credibility is key.

Powell was technical, correctly agnostic to stock market reactions, and exceptionally aware of the risks in a market extremely oriented towards eternal stimuli.

For market operators, a president with such an unpolitical and market-agnostic profile may not seem like good news. But it is. Too many investors play the “buy the junk” “the worse, the better” trade. That is, to expect poor macro data so that monetary stimulus is perpetuated. This carry trade leads market participants to bet on cyclical assets and inflationary themes while expecting stagnation and higher expansionary policies. And it is dangerous. A relevant proportion of the market reacts negatively to good macro data, a rise in wages and the strengthening of the economy, and should be criticised and urgently.

What Powell explained is very important. The path of rate increases is clear. In addition, the new members of the Federal Reserve arrive with a much more prudent position on monetary policy than those we have known in the past. The “Buy Anything” party is over. And this is good.

The U.S. economy can absorb a rate hike path to 2.75-3.00% in 2019 without a problem. In fact, if the economy could not absorb it, we should be very concerned about the kind of growth and investments we have.

The massive debt deck of cards created by extreme monetary policy is falling and the most fragile countries ignore it.

The key questions are:

- What do we do now with the $7.5 trillion of negative yielding bonds globally?

- Who will accept historic-low bond yields in emerging markets and in old Europe? Greece and Portugal have a lower short term yield than the U.S.

- Who believes that all European countries can finance themselves at lower rates than the United States, discounting inflation?

- Who buys high yield bonds with less than 300 points over Treasuries?

The answer is no one. Real market demand for these extremely expensive assets simply vanishes. The mirage of “high liquidity” disappears in front of any seller’s eyes.

I do not worry about the United States. The transmission mechanisms are very flexible and powerful. Less than 20% of the real economy is financed through banking, compared to 80% in Europe. In the United States, the entire financial sector makes mark-to-market valuations of assets. In Europe and other large economies they use “mark to value”. What does that mean? Excel spreadsheet estimates support everything.

Now we see the risk of the domino effect. Real demand evaporates for expensive “low-risk assets” (bonds), then equities fall, illiquid assets’ valuations are tested, transactions fall, then banks’ core capital erodes. Economies that grew accustomed to cheap and abundant U.S. dollar inflows then see the reverse. Fund flows go back to the U.S. regardless of investment bankers’ comments about value, growth or inflation. It is called “the sudden stop”. And it is essential to stop a bubble from being a systemic risk.

Back to the U.S., the Fed’s expectation of inflation is also very moderate. Core CPI of 2.1% in 2019 and 2020 is well below what inflationists fear. But, what is more important, the likelihood is that inflation expectations are revised down, not higher. The disinflationary trends of technology, debt and overcapacity are much more important than the inflationary temptations of policy makers.

The path of rate hikes is absolutely essential to reduce the enormous risk of bubbles creating a systemic risk. What I find hilarious is to hear some commentators say that the policy of the Federal Reserve is hawkish.

Raising rates to 1.75% in an economy that is growing 2.5% and almost in full employment while maintaining a nearly unchanged Federal Reserve balance sheet of $ 4.4 trillion is not a restrictive policy. It remains extremely expansive. Even if inflation expectations are met, the Federal Reserve will keep rates between 150 and 200 points below the curve in 2020.

Powell knows one thing. If the Federal Reserve does not accumulate tools now, while the economy is expanding, it will not have any weapon when recession hits. If imbalances are perpetuated, it will not only be a case of finding itself without tools, but, by then, monetary policy will not solve anything. Or do we think that lowering rates from 1.75% to 0% and increasing the balance sheet further will sort out the next crisis? No, it will not.

When I was presenting my book at the Federal Reserve Bank in Houston, one of its excellent economists made a very interesting remark: “Investors are worried about inflation or deflation, but they do not seem to worry about the risk of stagflation”. Because that is a more likely outcome in most G20 economies.

Welcome, then, a more technical message, a Federal Reserve president that feels less “trapped” by market volatility, and a more prudent policy. Ideal? Maybe not. But much needed.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the ECB continues to ignore the accumulated risks and the sovereign bubble. And winter is coming.

Chief Economist