I have commented several times on the errors of protectionism and trade wars. There is another problem. The major developed economies have allowed China to get away with its protectionism and interventionism measures because it was the engine of growth of the world economy.

Many talk about trade war as if it was something new and unexpected, and it is a basic error of diagnosis. The world has been in a trade war for years. The United States has denounced trade barriers imposed by China, the EU and other countries for many years, and the World Trade Organization did little about it. The 2017 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers had more than 70 pages of direct barriers imposed on the export of U.S. goods and services.

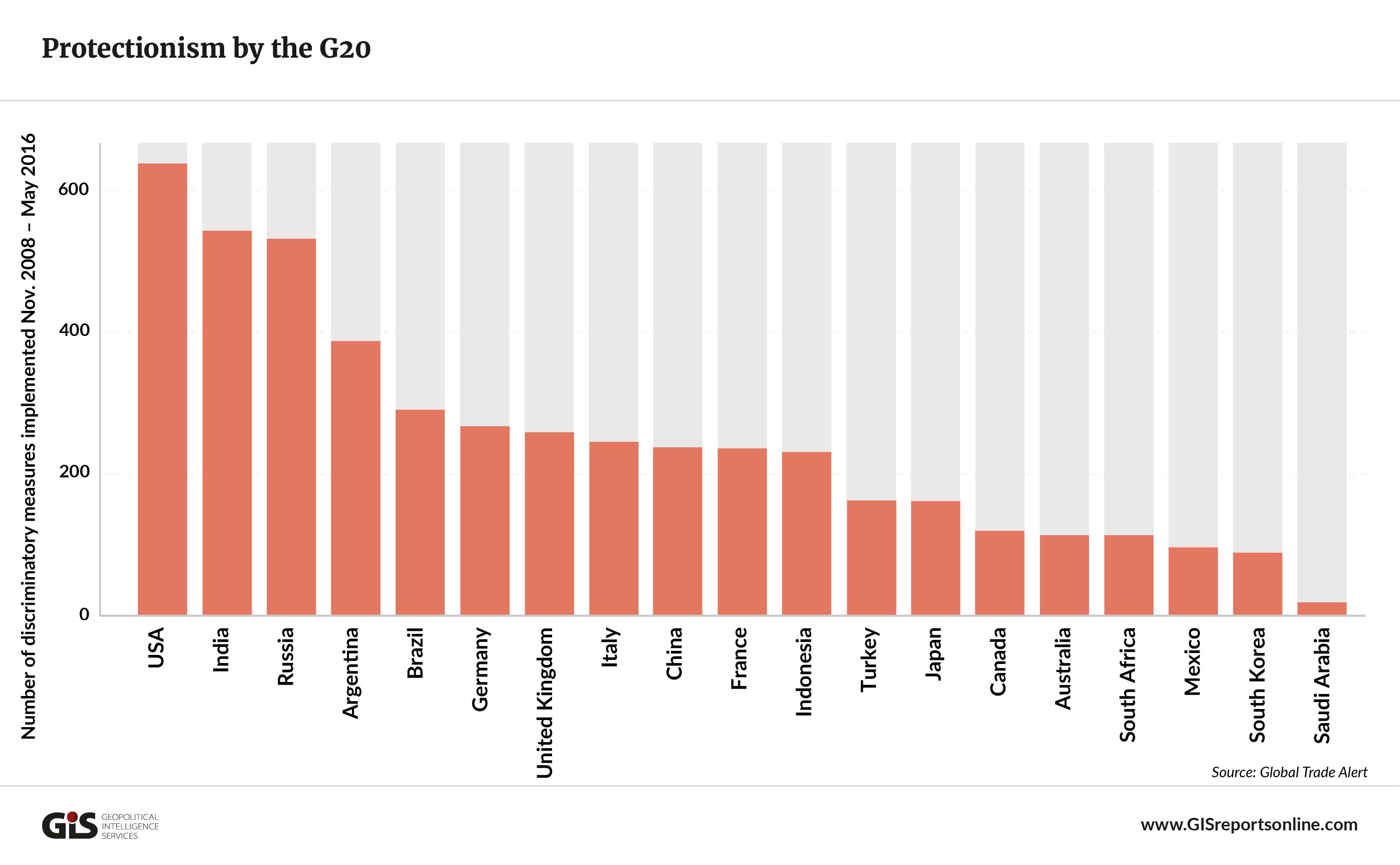

The United States has also imposed trade barriers in the past. From the 2002-2003 tariffs of the George W Bush administration to the highest rise in protectionist measures between 2009 and 2016. The Obama administration imposed more protectionist measures than any other G-20 country in that period.

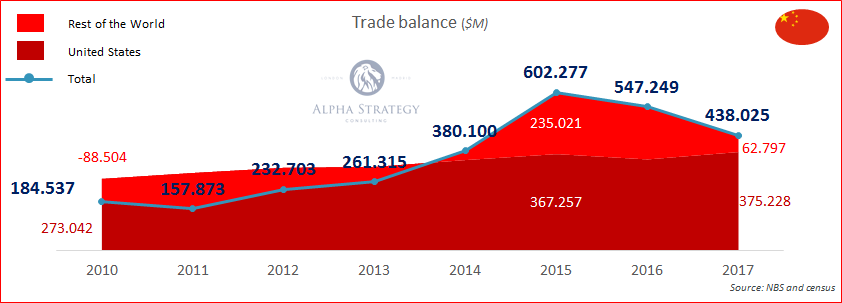

What the Trump administration is doing now is a negotiation tactic. Aggressive, bulldozer-type and, of course, questionable. But it is a tactic to address the massive trade deficit with China, the largest in the world, at $375 billion. The negotiation tactic is clear, as proven by the tariff moratorium on the European Union, Canada, Mexico and South Korea.

China needs the U.S. surplus more than the U.S. needs China’s trade and finances. And that is why the trade war will not happen. Because China has already lost it.

This is a duel at dawn in which it is most likely that no one will shoot … Because the pistols are loaded with debt, not with gunpowder.

The trade war will not happen for various reasons:

. China badly needs the surplus with the United States to keep its extremely indebted growth model, way more than the United States needs China’s purchases of debt of goods. China added more debt in the first quarter of 2018 than the U.S., Japan and the EU combined, and it has reached an estimated 257% of GDP. If it does not grow exports to its main customer, the U.S., its problem of overcapacity and debt soars, and the economy crumbles.

. China cannot win a trade war with high debt, capital controls and US exports’ dependence. A massive Yuan devaluation and domino defaults would cripple the economy.

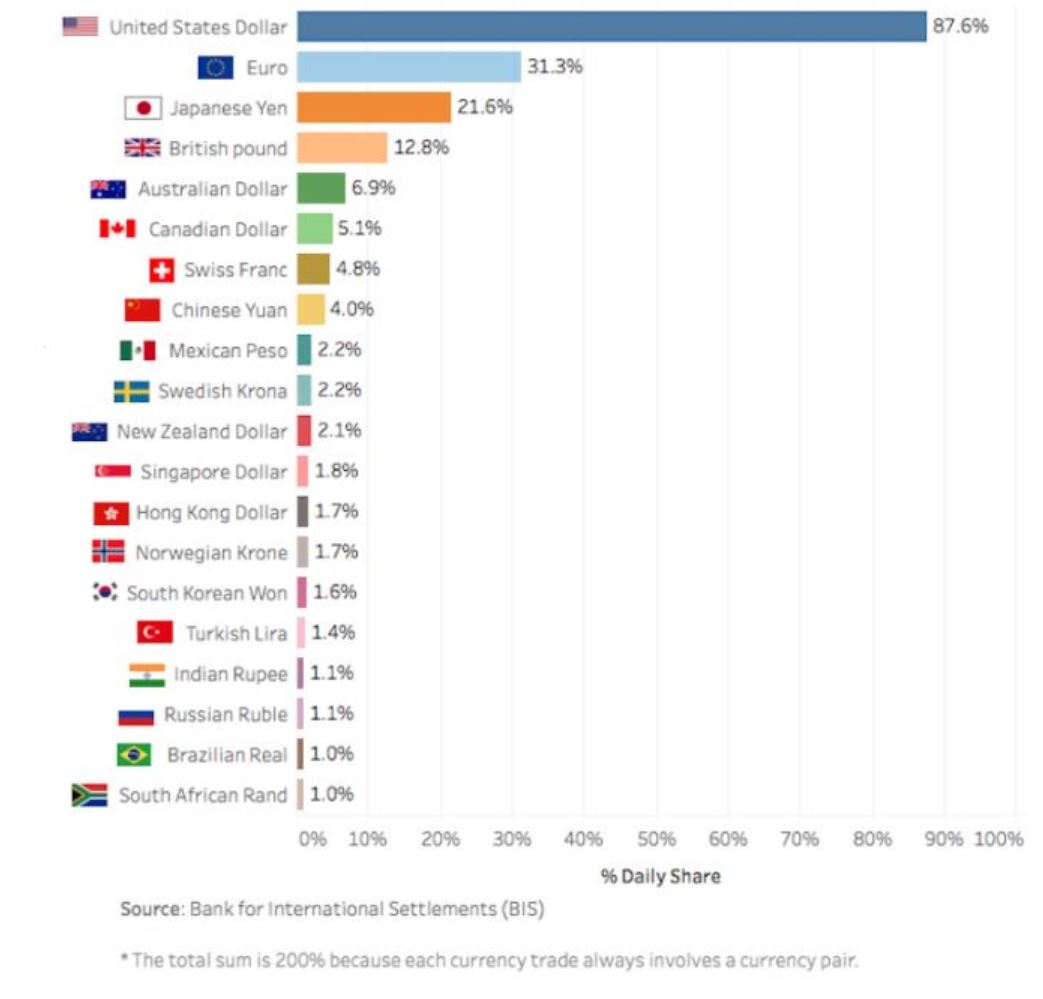

The U.S. dollar is the most traded currency in the world, and growing according to the Bank of International Settlement. The Yuan is 4% of currency trade.

. China’s currency is not backed by either global use nor gold. At all. It is as unsupported as any fiat currency, like the U.S. dollar, but much less traded and used as a store of value. China’s gold reserves are an insignificant fraction of its money supply. Its biggest weakness comes from capital controls and intervention. However, even with capital controls, capital flight has continued. $51bn outflows in the first quarter of 2018, according to Natixis.

. China does not have a nuclear option on the U.S. debt. For once, it is not the main owner of U.S, bonds, not even close (China is less than 8.6% of U.S. bonds outstanding). The United States can guarantee the demand for its debt issues even if China sells. But, in addition, China has increased its purchase of U.S. bonds by $168 billion dollars since the U.S. elections. If China sells its Treasury holdings, its own currency would massively appreciate and the domestic risks, lower exports, lower growth, outweigh the threat. Even if it sold, the demand for U.S. bonds has increased and when China has reduced Treasury holdings, Treasury yields have fallen. The Federal Reserve and the main U.S. Fixed Income funds could buy the bonds in a very short period of time, a week at most. Remember that 2018 has seen a record pace of inflows to U.S. Treasuries. $3.4 billion inflows in one week, with year-to-date inflows of $18.6 billion (data April 14th, 2018).

. China cannot maintain its growth – based on a huge debt bubble – if its exports fall. And its trade surplus with the United States has been growing while its trade surplus with the rest of the world shrunk. A drop in the growth of China’s exports would mean a collapse of foreign currency reserves. These reserves have been recovering a bit recently, but have fallen 21% since the 2014 highs.

A collapse in the reserves of foreign currency would accentuate the capital flight that is already taking place, which would lead to increasing the already disastrous capital controls in China, and with it, three effects. Lower growth, higher debt and the risk of a very important devaluation of the yuan.

For China, a trade war would be devastating.

Of course, there are important negatives for the U.S. but not as dramatic.

The United States exports very little (12% of GDP), so any threat that leads to a positive agreement is an exponential improvement. But the duel is loaded with wet gunpowder.

If Trump’s threats do not lead to a negotiated solution, the United States loses too. First, in its admirable path to energy independence, secondly, in consumption, third in jobs. A commercial war on technological products, steel and aluminium can generate a relevant added cost to exploration, renewables and technological products. This implies more expensive products, less consumption and less employment. The 2002 Bush Jr tariffs almost destroyed 167,000 jobs.

The U.S.’ twin deficit is also a challenge. Demand for U.S. dollars and dollar-denominated assets is high, but financing can lead to other challenges in the economy, especially credit growth to the productive sectors and risks of a recession. With a $21 trillion government debt and corporate leverage at multi-year highs, the risks are not to be dismissed.

The threat of trade war is not inflationary. Trade wars generate higher negative effects on growth, employment and consumption than the supposed protectionist effects governments seek to achieve. The price of metals, steel and aluminium have fallen since the tariffs announcements. So far, the industry is not affected by higher costs, but these are early stages. Additionally, the Federal Reserve has announced rate hikes with a very clear route. With rates at 2.75% -3% in 2020, the probability of inflation in commodities is very low. If we add to this the repatriation of capital generated by the tax reform and the evidence of a global slowdown, it means higher inflows of U.S. dollars.

China’s fragile debt-based growth model means it has already lost any possible trade war. So it cannot enter into one with empty threats. But we cannot ignore that it can also offset the estimated positive effect of the tax cuts in the U.S., and lead to a recession that would hurt the average citizen. The U.S administration knows that its pillars of support are taxpayers and job creators. And none of them wins in a trade war.

Both sides benefit from an agreement, and China cannot ignore the need to rapidly catch up on transparency, property and intellectual rights. That is why a full-blown trade war is more than unlikely.

Daniel Lacalle is a PhD in Economics and author of “Life In The Financial Markets”, “The Energy World Is Flat” (Wiley) and “Escape from the Central Bank Trap” (BEP).

Graphs courtesy BIS, GIS, Alpha Strategy.

In the case of China, it’s clear that we are the client. And the client is always right in the end.

if you have two countries with the same amount of debt to GDP, it is the one with lower growth that should worry. Yes, that is the DM in the world, not the EM. That is especially true for souther European DMs. Wake up, people, you cannot bath in the sun, drink all day and hope your debt magically disappears.

Nailed it. I’m from Spain and from my experience I can tell that the average Spanish thinks the state can provide them anything without any cost and the private companies are evil.

As you can imagine, the taxes to enterprises, freelances… are too high, thus the entrepreneurship is too risky and as a consequence is low.