While markets become increasingly bullish, oil prices are close to a “warning zone” where the barrel could be one -if not the only- catalyst of a major slowdown.

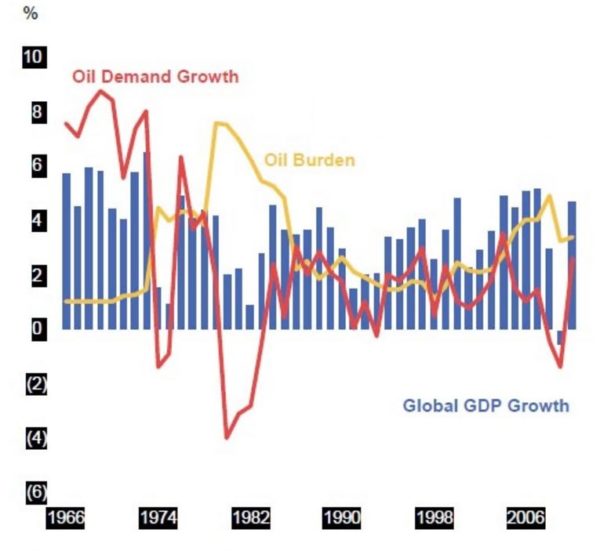

In my book “Escape from the Central Bank Trap“, I explain the concept of the “Oil Burden”. It is the percentage of global GDP spent on buying oil. It is often said that when the oil burden reaches 5-6% of GDP it can be a cause of a global slowdown.

The mistake that many make is to think that the oil burden is a cause and not a symptom.

In the past, we have seen that a period of abrupt increases in oil prices was followed by a recession or a crisis. However, not because oil prices rose rapidly, but because the dramatic increase in commodities’ prices was caused by a bubble of credit and excess monetary stimuli.

In reality, the oil burden is perfectly manageable at 5% of GDP because the energy intensity of GDP growth is diminishing. We are less dependent on energy to create growth in the economy.

Global energy intensity (total energy consumption per unit of GDP) declined by 1.2% in 2017, slightly below its historical yet unstoppable trend (-1.5%/year on average between 2000 and 2017 and -1.8% in 2016). In fact, global energy intensity is down 54% since 1990.

So the problem is not the oil burden by itself but the cause of the price spike.

When oil prices rise abruptly we should be concerned, because they can cause a domino effect on the real economy. When the reason for the price increase is not fundamental, we have a major problem.

Why are oil prices rising abnormally in recent months?

- Supply manipulation. Despite inventories falling, OPEC has maintained a tight grip on supply, unjustified from the premise of an oil glut that is inexistent or from the premise of “low” prices, which are comfortably above $70 a barrel. By being greedy and keeping supply tight, OPEC is hurting its customers -mainly Europe- and creating the foundations of a forthcoming bust cycle.

- Iran sanctions. The reality is that Iran sanctions have a very small impact on the supply market, 600,000 barrels a day reduction in exports. These could be easily offset by higher OPEC and non-OPEC output, but if supply limits remain, the impact on marginal prices is exaggerated. OPEC produced 32.79 million barrels per day in August, up 220,000 bpd (barrels per day)from July’s revised level and the highest this year. However, the lid remains on the maximum output despite Libya coming back to normalized levels.

- Venezuela production collapse. The Maduro regime’s disastrous management of the state-owned PdVSA has led the country to cut production to 1.4 mbpd (million barrels per day) and likely end 2018 at 1mbpd. The combined impact of Venezuela and Iran could have easily been offset by higher Saudi and OPEC production, helped by higher non-OPEC output.

- Inventories continue to fall. Crude inventories fell for the fifth consecutive week. Stocks are at 394.1 million barrels at the end of the week (22nd Sept 2018) in the US, the lowest level since early 2015. OPEC cannot hang on to the message of an oil glut. It is not evident anywhere anymore.

- US oil production continues to rise and provide positive surprises. U.S. crude oil production is expected to rise 1.31 mbpd to 10.68 mbpd in 2018, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Production will average 11.7 mbpd in 2019.

- What about demand? High prices are already affecting oil demand in India and Europe. India total demand fell month-on-month in July. Demand was 358 kb/d lower, and demand growth has stalled. In Europe, a slowdown in industrial production and consumer spending is evident, while the emerging market crisis and China slowdown are also clear risks to the optimistic expectations of demand growth posted by OPEC and the EIA.

The risk, therefore, is that too much greed may break the camel’s neck. Imposing artificially higher prices on the world through supply management always backfires. Many oil analysts wonder why oil is not at $100 a barrel with all the above-mentioned issues.

The supply management’s desired “boom” is smaller than expected due to lower energy intensity and high global debt, and the risk of an abrupt bust is exacerbated because price increases are not based on fundamentals.

The global oil burden will rise to 3.1% of global GDP in 2018 from 2.4% in 2017 and -if Brent goes to $80 for an entire year- could soar to 4% of global GDP. This is deemed as manageable by most analysts. However, “manageable” is a scary concept that was used numerous times in the past before a bust.

The risk for the economy may not be the oil burden in itself, but a rising oil burden that is entirely driven by supply manipulation, disconnected from supply and demand reality and affordability.

If you believe rising oil prices prove the success of OPEC’s boom cycle creation, be careful about the bust. It will be self-inflicted.

Let me comment on a few of your points, if I may.

“Global energy intensity (total energy consumption per unit of GDP) declined by 1.2% in 2017, slightly below its historical yet unstoppable trend (-1.5%/year on average between 2000 and 2017 and -1.8% in 2016). In fact, global energy intensity is down 54% since 1990.”

Perhaps you are right. But my issue is with the GDP measure. When governments consume so much of the savings generated by the private sector and its misallocated spending gets measured as an increase in GDP, I do not have much faith in the validity of the measure. I would argue that much of the increase in GDP is a con that was driven by a massive increase in money and credit. While I agree that productivity has reduced waste, which translates to lower energy intensity per unit of real production of goods and services, the relationship to GDP is not what we may believe it to be.

“Despite inventories falling, OPEC has maintained a tight grip on supply, unjustified from the premise of an oil glut that is inexistent or from the premise of “low” prices, which are comfortably above $70 a barrel. By being greedy and keeping supply tight, OPEC is hurting its customers -mainly Europe- and creating the foundations of a forthcoming bust cycle.”

Almost all OPEC nations are past peak production and some of the current daily production is driven by the use of water drive, horizontal drilling, and other enhanced-recovery techniques that borrow from the future. Greed is a false charge because all of us choose that which we prefer from other options. The fact that we want OPEC countries to produce oil without full compensation is no less greedy than the individuals who set the targets turning down the pressures to prolong production as long as possible.

“US oil production continues to rise and provide positive surprises. U.S. crude oil production is expected to rise 1.31 mbpd to 10.68 mbpd in 2018, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Production will average 11.7 mbpd in 2019.”

American oil production is driven by cheap credit, not economics. The shale miracle is a scam. While shale production makes a lot of sense in small areas of some formations, most of the reservoirs in those formations are not economic. It is no surprise that the shale sector has destroyed hundreds of billions in capital. And it will not be a surprise when a wave of defaults destroy investors and lenders who bought into the shale story.

My question is a simple one. What happens to the American dollar when the illusion of energy independence is shattered? What happens to all of that debt and the unfunded liabilities? Please note that the US is not alone. Most countries have created an illusion of sustained prosperity by printing money and issuing credit. Eventually, all fiat currencies will start to collapse and at that point those people who decided not to trade precious oil for little pieces of paper that were created by a printing press are going to look a bit smarter, notwithstanding that they will also be doomed by bad government policies that ignored econmic reality and sound monetary theory.

Your arguments seem quite close to some of the peak oil myths I criticise in The Energy World Is Flat. However, the US dollar would strengthen in your case because currencies are not backed by commodities. Thanks a lot.