Facing the evidence of sluggish growth, governments are calling for massive infrastructure plans as the answer to a weak economy and a way of boosting growth. However, the reality of most large government infrastrcuture plans is actually more than disappointing.

Facing the evidence of sluggish growth, governments are calling for massive infrastructure plans as the answer to a weak economy and a way of boosting growth. However, the reality of most large government infrastrcuture plans is actually more than disappointing.

Over-investment in infrastructure can be damaging. 55% of Chinese infrastructure projects are estimated to destroy economic value, and nine out of ten large infrastructure projects are over budget. On average, rail projects are 45% over budget, according to Mahoney et al (Infrastructure can be a bad investment, 2016).

The main factors that make public infrastructure plans fail to deliver the desired levels of growth are:

- Lack of prudent planning. Overestimate demand, a typical public sector trait, and underestimate debt burden.

- Rush to spend. Most infrastructure plans become a race to see who spends more and earlier, in order to maximize budget (another typical trait of the public sector).

- The belief that building something generates growth no matter what. Ignores the cost of capital, working capital and rising debt.

Despite the evidence from Japan, the European Union and China, governments continue to believe in a fiscal multiplier of government spending that has not been evident for decades. The real conclusion is that multipliers are very low or negative in open and indebted economies, precisely because they come from previous excesses created by those same “stimulus” plans (How big (small?) are fiscal multipliers? Ilzetzk et al, 2013).

Even if we accepted positive fiscal multipliers, the empirical evidence of fifteen years shows a range that, when positive, moves barely between 0.5 and 1 at most … and in most countries, it has been negative (Fiscal Multipliers, Size, Determinants and Use In Macroeconomic Projections, Batini et al).

The perverse incentive to spend the money of others to offset the excesses of the past generates an increasing misallocation of capital to low productivity sectors and the current expenditure is financed with higher taxes to high productivity industries.

The so-called expansionary policies turn into a huge transfer of wealth from the productive sectors to the unproductive ones, impacting potential growth and weakening the economy.

Japan, the European Union, and China are not examples to follow, but to avoid.

Between 1991 and late 2008, Japan spent $6.3 trillion on “construction-related public investment”, which significantly contributed to its stagnation, high debt, and weaker productivity growth (If You Build It . . . Myths and realities about America’s infrastructure spending, Edward L. Glaeser, 2016).

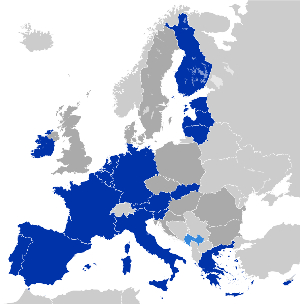

The Eurozone example is not positive either. A huge stimulus in 2008 in a “growth and employment plan”. A stimulus of 1.5% of GDP to create “millions of jobs in infrastructure, civil works, interconnections, and strategic sectors”. The result? 4.5 million jobs were destroyed and the deficit nearly doubled. That was after the crisis because between 2001 and 2008, money supply in the Eurozone doubled. The Eurozone has been a chain of stimuli since day one.)

The so-called “Juncker Plan” or “Investment Plan for Europe” hailed as the “solution” to the European Union lack of growth was the same. It raised 360 billion euros, many for white elephants. Eurozone growth estimates were slashed, productivity growth stalled and industrial production fell, and now the ECB is calling for a “new stimulus plan” because the Eurozone economy is struggling.

As pointed out by the study by Ansar et al (Does infrastructure investment lead to economic growth or economic fragility? Evidence from China. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 2016), China’s infrastructure investment model is not one to follow for other countries but one to avoid.

Infrastructure spending can be positive, only if it satisfies a real demand, and if the investment is undertaken with strict budget control and realistic economic return expectations. That is why, in most cases, infrastructure projects should not be centrally planned or government sponsored, let alone financed by the public sector. It can be easily used as a way to mask low growth and inflate GDP artificially.