The G20 summit has not generated unexpected or significant headlines and, of course, is not a catalyst for a relevant change in the global economic trends. The United States and China have only agreed to postpone tariff increases, but no real trade agreement has been reached.

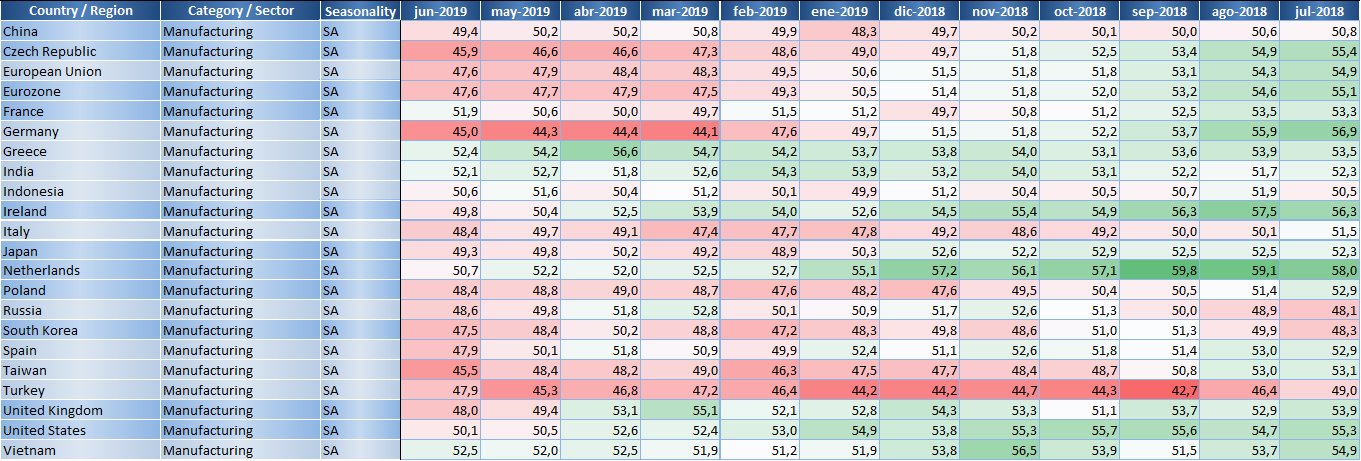

If we look at the last G20 meeting conclusions, nothing has really improved. Plans to introduce new tariffs are delayed, and the result is exactly what happened in the previous G20. The real news is the evidence of a manufacturing recession.

Markets have reacted strongly in a relief rally because the trade dispute did not get worse. The safest assets, such as gold, fell while the stock markets rose despite a widespread disappointment in manufacturing PMIs. And therein lies the danger. Many investors are betting again on monetary policy as the only factor to drive markets and risky asset valuations higher.

It is difficult to think that the agreement in the G20 will improve the global economic outlook, mainly because the weakness of the Eurozone or China and the slowdown of the manufacturing sector have nothing to do with the so-called trade war, but with almost a decade of excess in demand-side policies, which have perpetuated overcapacity, increased debt and made economies less dynamic by zombifying the low productivity sectors through low rates and constant refinancing of non-performing debt.

If there is any positive news for world economic growth, it has not come from the G20, but from the agreement between Mercosur and the European Union, after twenty years of negotiations. The European Union liberalizes its agricultural, industrial and service imports and supports an improvement that can be significant for the economic growth of the countries integrated in Mercosur, as well as helping the EU revive its stagnant economy. Or at least try.

Unfortunately, these agreements do not reduce the risk of high indebtedness or excess capacity. The great problem of multilateral agreements is that they often disguise the errors of debt saturation and political spending and sometimes increase those mistakes.

We are living a kind of “Groundhog Day”, the constant repetition of something we have already lived: a few smiles, a handshake, a couple of tweets, reasonably broad and vague messages, but little in terms of concrete measures.

Our estimates of economic growth and corporate profits have not improved after the G20, and it is worth warning of the risk of complacency when macroeconomic indicators worsen and investors increase exposure to risk. What emerges in many cases of this different trend between macro indicators and market valuations is that there is only one synchronized bet: More central bank injections. Investors hoping that data will continue to worsen so that central banks will inject more liquidity and lower interest rates.

At the very least we should be cautious in pro-cyclical exposure. Macroeconomic data show the evidence of the slowdown and risk of stagnation.

After more than 20 trillion dollars of stimulus, massive deficit spending and large incentives to increase capex and debt, manufacturing ind¡ices are in contraction. Businesses have plenty of available capital at low cost, but face the prospect of weakening demand and zombification, so manufacturing is showing one of the worst side effects of cheap money: stagnation from debt saturation and widespread excess capacity.

No trade war truce or central bank quantitative easing is going to change this trend because central planning and demand-side policies are the culprits of stagnation, not the solution.

Articles ,right place right time

Great articles, right place and right time