The great debate in mainstream economics these days is centred in the weak level of investment and consumption seen throughout the current recovery. However, it strikes me as ironic that there is almost no debate in the Keynesian world about the diminishing returns of financial repression and the increasing loss of credibility of demand side policies.

There was a time in which the average citizen would see inflation as a fastidious side effect, as an anomaly caused by unclear factors. The veil was lifted in the last eight years. In the past eight years the US, for example, has seen the largest transfer of wealth from savers and the middle class to the government. $1.5 trillion in new taxes, $9 trillion in new debt and $4.7 trillion in central balance sheet expansion for a mere $3 trillion real GDP expansion.

Financial repression was the only tool to solve imbalances of the post-Bretton Woods world. But in the past eight years, financial repression was taken to an extreme never-seen-before.

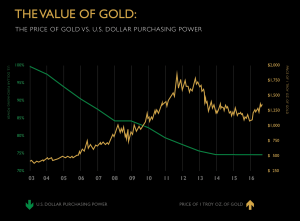

Citizens may not understand economics and the forces that affect their wealth and disposable income, but they sure do perceive the hole in their pockets. Financial repression has obliterated the purchasing power of the currency and at the same time made it more difficult for the middle class to improve their wealth, as it becomes more and more challenging to save and the returns of those savings are slashed with the subsequent 600 cuts in interest rates we have lived in the past decade.

(Source here)

Keynesians will say that financial repression is a necessary tool to improve the economy and solve imbalances created by one or another financial crisis. What they always forget to mention is that those crises have always been caused by the artificial creation of money without any real support. The boom and bust cycles are more frequent precisely due to this constant and uncontrolled use of monetary policy to cover structural problems.

The same mainstream economists will also say that the unintended consequences of financial repression are offset by the so-called “wealth effect”. Yes, the value and purchasing power of money are distorted and devalued, but stock markets compensate that effect and house prices rise. There is a problem. The vast majority of the hard-working middle class do not play the markets, and the constant boom and bust cycles, added to a weakening of purchasing power, makes it increasingly more difficult for citizens to become homeowners. In effect, 80% of US household wealth is not in stocks, financial assets or houses, but in deposits, which are being eroded by the policy of destroying savings to artificially subsidize the indebted and inefficient.

Mortgages may be cheaper, but it does not matter when your credit profile is weak and your salary does not reach to cover the bills. Add to financial repression tax increases and the “wealth effect” is felt less and less by the backbone of the economy, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and families.

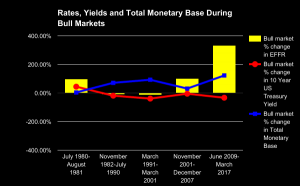

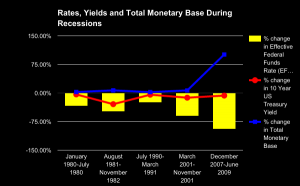

The above chart shows clearly why the middle class and SMEs are left behind in financial crises. The abrupt change in money supply and the lowering of interest rates reaches the weakest parts of the economy last, but when it goes the other way round and money supply collapses, it is the middle class and SMEs who suffer first through the credit crunch and inability to cover costs.

Furthermore, the middle class is not only finding itself as the payer of the bill of each new credit boom cycle, but it also finds it increasingly more difficult to participate in the recoveries, because families and SMEs are suffering the increase in the tax burden to cover the deficits created by wasteful governments and the bailouts of rent-seeking industries -through massive subsidies- and inefficient financial entities.

Not only is it more difficult to participate in the questionable wealth effect created by financial repression, but it is more risky, because the average citizen is a conservative investor looking at the long-term, and is rarely able to actively manage a portfolio to preserve capital and hold on to gains.

This is the reason why mainstream economists scratch their heads when voters react against governments that boast of economic recoveries that the average family simply has not seen. Because when governments forget sound money as a key principle, and the importance of defending savers, the voter will react against the rulers, even if they do not understand that financial repression is an active policy, not a coincidence.

Think about this, today central banks are increasing money supply -printing money- at a rate of $200 billion per month… and we are not even in a recession. With stock market valuations at all-time highs and bond yields at historic lows globally, imagine the side effects when this ends.

Today’s savers need to look for ways to reduce risk and preserve wealth, beating the inflationist agenda, and that is extremely difficult because the small investor’s tolerance for volatility and understanding of valuations is logically limited. That is why more and more small investors, looking to protect their hard-earned wealth, will look at alternatives to deposits that are as far away as possible from the temptation of manipulating money supply of the governments. As the only monetary policy used in the past 50 years generates ever diminishing returns even for the objectives of Keynesians, the urgent need to return to sound money measures and protection of the middle class becomes critical. Because the next bust will not be covered with lower rates and more money supply after 600 cuts and $20 trillion of liquidity.

Daniel Lacalle is a PhD in Economics, fund manager and author of Escape from the Central Bank Trap (BEP), Life In The Financial Markets, and The Energy World Is Flat (Wiley).

Special thanks to Robert Elway. Images courtesy of @RoslandCapital1