“The debt compromise is like eating a Satan sandwich” Emanuel Cleaver

Yesterday I heard again a sentence that tends to be repeated frequently: “Deficits support growth”. It assumes with his claim that increasing deficits helps economic recovery, rather than see that such recovery is much slower and fragile precisely because of the large deficits and the cost of financing them with taxes.

The nascent recovery that I have been commenting for a few months has a very clear threat. The over-indulgence of debt accumulation just because cost is low, which leads us to the risk of spending a long time stuck in pedestrian growth levels.

The argument in favour of forgetting the debt problem is heard every day.It goes like this: What matters is growth. As long as economies get out of recession, and cost of debt is low, governments should not worry, as little by little indebtedness will be reduced because the denominator, GDP, increases. All is fine.

This argument has only three drawbacks: the saturation threshold, destructive debt and volatile cost of debt.

- What is the threshold of debt saturation? I have mentioned it several times. The point at which an additional unit of debt does not generate economic growth, but simply stagnates the economy further. This threshold was surpassed in the OECD, between 2005 and 2007.

- What is destructive debt? It’s the debt generated by unproductive current expenditure, which produces no positive effect on growth and perpetuates a system that confiscates and engulfs the real economy through taxes, detracting investment and annihilating consumption. In the European Union or the US, a structural deficit of nearly 4% of GDP.

- Volatile cost of debt. What makes us think that bond yield and cost of debt are going to stay low forever? We have seen U.S. bond yields rise by 64% so far this year and German soar by 49%. Of course, from a very low level, but the reality is that bond yields can not be kept artificially low forever. And that’s when e see debt shocks, because the outstanding debt accumulation increases while low yields are unsustainable.

‘Cheap’ public debt is not a free pass to spend. In fact ‘cheap’ is a misnomer, since it assumes that there is no cost of opportunity in private investing or saving.

Cheap is dangerous. Think of the perverse situation in a country like Japan, with a debt of over 200% of GDP, where the country’s financing needs are over 60% of GDP in 2013. Its ten year bond yields only 0.7%, so the country’s incentive to reform is very low… because debt is cheap… Yet if there is an increase in the yield of a 100 basis points it would endanger the entire economy. Japanese public debt, cheap or expensive, is more than 24 times the country’s fiscal revenues.

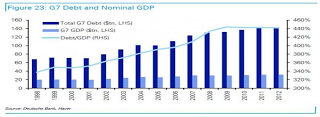

On the debt saturation problem, Deutsche Bank recently showed the impact of the last five years:

The G7 countries have added almost $18 trillion of debt to a record 140 trillion, with nearly five trillion from central banks’ balance sheet expansion, to generate only a trillion dollars of nominal GDP.

That is, in the past five years, to generate a single dollar of growth we have “spent” $18, thirty percent from central banks. All this while maintaining the system’s total consolidated debt at 440% of GDP.

This ‘investment’ in growth that is supposed to be accomplished through astronomical deficits, debt and aggressive expansion of central banks simply does not bear fruit. Of course, many say that the solution is to continue doing it until it works. But the system becomes increasingly fragile and subject to massive shocks with the slightest movement of interest rates.

These pedestrian growth levels also occur in the middle of a fierce financial repression period. Devaluations and interest rate cuts discourage savings, and push the system further into debt. Money is “cheap” and saving is considered “silly”. But meanwhile taxes are raised and disposable income is destroyed.

It impoverishes the population in four areas: savings, their profitability, real income and consumption capacity.

This leads to a much weaker system, because the fixed costs, public spending, multiplies in cyclical economies, leaving very little room for manoeuvre in hard times . And then governments say it is a revenue problem, as if an administration can be handled waiting for the bubble to return. George Osborne, in the UK, said “a government that spends 720 billion pounds a year cannot be called a government or an administrator, it is unacceptable.” Notice he did not say in a moment “it is a revenue problem”, which is what we hear in Europe all the time. Revenues come with economic activity, and if we suppress it through taxation to finance an unacceptable expenditure, this economic activity will not improve.

Think of Spain, which is showing signs of recovery. Debt to GDP has reached 92%, increasing by 17.16% over the same period of 2012 and above the full year target of 91.2%. However, the Spanish Treasury plans to save about 5 billion euros on cost of financing. Why? The cost of debt has dropped more than financing needs have grown. Phenomenal. The concerns about the European Union is gone, the European Central Bank helps, the economy is slowly coming out of recession … All true. And the much needed reforms have stopped almost to a halt because debt is cheap. A bad incentive.

However, the annual financing needs of the economy are at historic highs, around 70 billion euros. Imagine even if it as 30 billion if Spain reaches its ambitious 2015 goals. Even so, the country relies on an environment of extreme low rates not to suffer a debt shock.

But imagine that the low yield party continues, and the Japanisation of European economies deepens. If we, as Japan, absorb the vast majority of our debt, we can achieve the effect of deceiving ourselves and lowering the cost artificially to unacceptable levels under normal conditions (such as the 0.7% of the Japanese ten year bond) Hurray! What will happen? That the perverse incentive to increase spending, not to reform the economy and make debt shoot up to 220% of GDP is too sweet not to be taken by the government. And then the problems become insurmountable, because European economies are not Japan in any sense, from labour to exports or industry.

But, imagine that this debt accumulation “does not matter” because we’re putting it in our pension plans, in our investment funds and it finances our airports, highways, hospitals, schools. It’s the social contract, right? The only contract signed by the unborn to pay the privileges of the living.

The problem is that such social contract sweeps away disposable income and savings in financial repression and taxes to finance public expenditure. In The EU it exceeds 40% of gross domestic product.

The absolute costs go up because it is always deemed as “little”, and the unit costs also soar because the population ages and fewer taxpayers contribute to that imaginary contract. So the economy stagnates. Debt grows. And one day, everything explodes. By then, economists will say that the solution is a devaluation or a debt-haircut, which is to impoverish the entire nation again, destroying the pension funds and savings.

In the United States, reverend Emanuel Cleaver called the debt ceiling negotiations the “Satan sandwich” , because among the bread slices there is nothing. The reverend’s error was to think that the country can afford eternally a deficit of almost 800 billion, despite stimulus, modest growth and some job creation. Spain’s mistake would be to think it’s time to relax adjustments because the economy has started to grow. An 0.6% growth of GDP with an increase of 6-7% in debt is simply unsustainable.

Now that we see the light at the end of the tunnel it is precisely no time to stop the reforms. It is essential to address the expenses and pay extreme attention to this accumulation of debt, to avoid shocks when yield-seeking euphoria stops, because as we dedicate our efforts to justify every useless expenditure as “small” and debt as “manageable”, the system becomes more fragile. And risk accumulation eventually bursts.

By then … governments will blame the markets.