“If technologies have economic merit, no subsidy is necessary. If they don’t, no subsidy will provide it”. Jerry Taylor.

“Governmental subsidy systems promote inefficiency in production and efficiency in coercion”. M. Rothbard

Category Archives: Spain

Markets expect a full Spanish bailout

(This article was published in El Confidencial on July 23rd 2012)”Defeat? I do not know the word”. Margaret Thatcher.Here come the shorts. It was obvious. Everyone prepared for a dose of QE from the Fed and the ECB, and when it didn’t happen, on Friday 75% of orders were better to sell.

Spain moves closer to a full bailout. Congratulations, we did it. Years of nonsense saying “we don’t have a problem of public debt” and “we have less debt to GDP than Japan” while our ability to repay was destroyed with wasted money on phantom airports, irrelevant statues, and high-speed trains with no passengers. The Ibex 35 plummets; no one invests in our bonds and the spread to the Bund rockets to 610 basis points. But do not think everything is discounted and that a bailout will be positive.

“There is no money”

The Spanish government in 2011 had fiscal revenues of 377 billion euro, about 7 billion more than in 2009. That means that in the middle of the crisis, with tens of thousands of businesses closing and unemployment rampant, revenues not only remained at a monstrous 37% of GDP, but increased. I estimate revenue of 385 billion in 2012. In other words, there is plenty of money. And there is liquidity, with hundreds of billions provided by the ECB. The only thing where there is no more money for is the public spending bubble, which has soared to 470 billion.

The recent demonstrations, which are perfectly legitimate, must take into account this problem. Today’s cuts come from past excesses.

It is amazing to see that citizens throughout the entire EU seem to presume “good intentions” to those rulers that bankrupted countries through reckless spending, but accuse of “bad faith” to those that deal with paying the bills and cleaning the accounts. The widespread perception that money is free, that spending is good and saving is bad.

Slash political spending now

Maybe it’s a matter of perspective. Arthur Laffer said that he would reduce the deficit in one hour. I am more conservative. Give me the Spanish budget and a red pencil, and I will reduce the deficit to zero within a week. I accept getting paid in government bonds.

What terrifies me is that everyone in Spain seems to have given up and just looks for excuses. It is irresponsible to dismiss as alarmists those who alert of the gravity of our problems. In fact, those who continue to say that “we are on track”, “we need more time” and thinking that this crisis is temporary are doing a huge disservice to the country. The VAT and tax increases will not be “absorbed by companies without affecting consumption” because corporate margins are at bear minimums, and we saw that consumption does fall as in 2010 with the previous VAT increases.

Has Spain given up?

The market does not “put pressure on Spain.” Investors do not buy because the risk of default is too high. Just look at the number of contracts traded on Spanish debt. Less than 40% compared to historical levels.

From a market perspective, there are three issues that concern me tremendously, issues that differentiate us from Italy, and unfortunately place us in the same risk as Greece or Portugal, but with a much larger corporate debt:

-Spanish governments always focus their economic measures on revenues (taxes). 61% of the measures adopted so far are expected increases in fiscal revenues.

–The cuts are not real cuts, but slowdown of the increase in spending. I read that the changes in the implementation of the Dependency Law “will allow a slowdown in cost increases estimated at about 3 billion euro”. I repeat, “a slowdown in expenditure growth”. Not cuts.

-Even with the new measures deficit is set to be around 6.5% in 2012, and the government continues to listen to advisers who say that everything will improve next year, as exports will help the economy and they need time to carry out reforms. It’s not true. The economy will not improve in 2013, nor will Spain export enough to cover the structural primary deficit- a key difference with Italy. And no, we have no time.

The perception that this is a temporary issue that can be sorted out increasing revenues is a huge mistake similar to that made by those who said in 2009 that “the worst of the crisis is over.”

¿Full bailout? No thanks. The example of Greece, Portugal and Ireland

We have seen this week a disastrous debt auction which, at the close of this article, has put the 10-year bond touching 7.2% and the spread to the Bund at 610 basis points. And I hear voices crying out for a full bailout and the ECB buying bonds as a great idea.

However, a full bailout does not involve anything positive. Do not expect an intervention to dismantle the bloated regional governments or to encroach on political spending. Moody’s had doubts on Thursday that Spain has any real chance of taking harsh measures on the regions. In fact, the Budgetary Stability Law itself establishes “hard” corrective measures that involve publishing a report and s written warning to the President of the region. Hardly agressive.

Intervention? Once the 10-year bond is up to 7% …

Unfortunately, the bailout process – including the “placebo” effect of useless massive purchases of bonds by the ECB- neither solves the crisis, nor calms markets, nor lowers bond yields unless the economy returns to competitiveness and political spending is slashed. Interestingly, political spending was not touched at all either in Portugal or Greece.

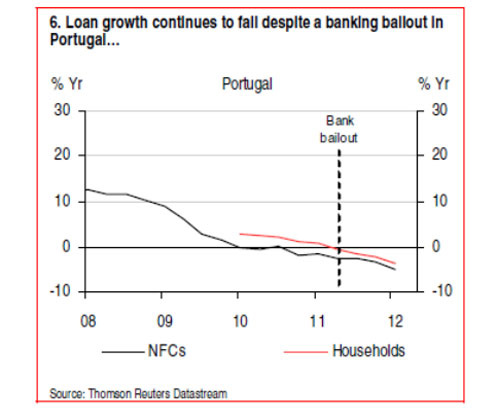

Greece and Ireland acted immediately and asked for a bail-out. Portugal took over five months to officially request one. In all three cases, the ten-year bond soared to 8 to 8.5% when the bailout was requested.

But once the bailout was in place, ten-year bonds just kept rising and the rating agencies downgraded the three countries to junk status. None of the countri

But once the bailout was in place, ten-year bonds just kept rising and the rating agencies downgraded the three countries to junk status. None of the countri

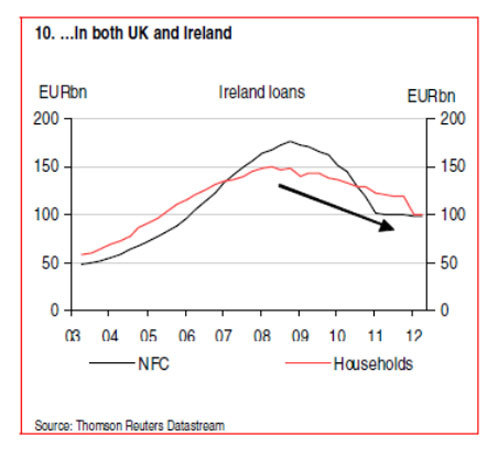

The few debt issues in Portugal and Greece were meagre 3-6 month paper, and Ireland was only able to return to the market almost two years after the bailout also with short-term paper, and that was after cleaning aggressively its banking system. The Portuguese 10-year bond is today at 10%, and the Irish is still at 6.3%.es had access to the credit market.

The time from applying for pre-bailout to downgrade to junk bond lasted between four and ten months for the three countries mentioned. Today, none of the bailed-out countries has seen a recovery of credit to the real economy.

Stocks are not discounting a bail-out

There are no “defensive” stocks with “exposure to emerging markets” and “low PE” when a country is bailed-out. Stock markets in Portugal and Greece fell by 44% and 65% respectively, a collapse almost as large as the pre-bailout fall. And we must bear in mind that, despite the poor performance of its stock market year-to-date, Spanish companies are still highly leveraged, a 200% of GDP in private debt, which comes in many cases from IOUs of the state for unpaid invoices.

The effect of a bailout for Spanish companies could be much higher than in Portugal or Ireland because of the huge refinancing needs in 2014, accounting for almost 35% of all corporate bond issues in Europe in said year. Without access to credit markets, companies would be forced to do more asset sales, dividend cuts and dismissals.

Bail-out means massive cuts

Do we want the ECB to buy Spanish debt? More “pretend and extend”. Pack and disguise. We did not learn from the past and the subprime crisis.

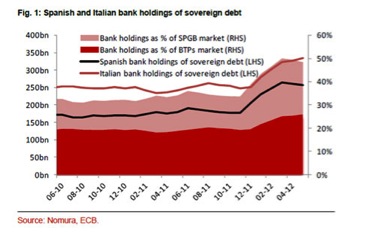

What has been the benefit so far of the massive purchases of Portuguese, Spanish, Italian and Greek bonds than loading the ECB with losses of 56 billion?, Nothing else but making the ECB the most indebted central bank … and no positive effect either on bond yields or the economy of the countries. “Watering the wine” to make it appear that there is more quantity in the barrel.

What has been the benefit so far of the massive purchases of Portuguese, Spanish, Italian and Greek bonds than loading the ECB with losses of 56 billion?, Nothing else but making the ECB the most indebted central bank … and no positive effect either on bond yields or the economy of the countries. “Watering the wine” to make it appear that there is more quantity in the barrel.

Want a full bailout? Not if we look at the example of our comparable countries. If you think that what we have now in Spain is “austerity”, when there is at best a modest adjustment, a full-scale rescue implies all social costs are axed. Severe cuts in pensions and the number of civil servants, raising the retirement age, much higher tax hikes and a collapse in GDP of between 3% and 3.5%. Do not forget that Ireland, the “good example”, suffered a fall in GDP of 7% in a year.

Internal bailout

What Spain needs is an internal bailout. If the government is right and there is “no money” and there is a national emergency then they have to be consistent and cancel the aid to banks, imposing debt to equity swaps to its debtors, cancel all subsidies and grants provided by the government (close to 14 billion a year), close all duplicative councils and pay politicians 50% of their salary in government bonds. Curtail spending now. Immediately.

I do not want a bailout because we do not need it if we cut spending. I do not want the ECB infected with Spanish bonds in exchange for giving away sovereignty because we can show that investing in Spanish debt is a good idea if we adapt expenses to income and stop calling for default and “odious debt”.

Spain can solve its problem, which was and is excessive spending. And then we will see the huge positive qualities of the Spanish economy, with excellent companies that can continue to export and can create jobs if we lower taxes and attract capital, not if we throw investments away.

We must not surrender Spain to the lenders. The ECB and the troika do not rescue, they do not support, and they do not donate. They lend in exchange for much larger cuts. And it doesn’t work, it only impoverishes. It has been proven by previous bailouts and all interventions of the IMF since 1978.

The red pencil to slash unnecessary spending is needed now. I provide the pencil if needed.

Rescued banks and subsidized companies, a bad combination

The market had high expectations ahead of the announcement from Spain of new economic measures, but the comments in London are almost unanimous. The measures to reduce the deficit and the ones leaked for the electricity sector follow the same principle: take funds from the efficient to maintain the subsidized. It’s easy, as value-added tax revenues have disappointed due to alleged “cheating,” all citizens who do not cheat must compensate for the lost revenues.

Raising VAT is a measure that does not work as seen with previous VAT increases, which generated less revenue. However, it would have been acceptable if it had been accompanied by immediate cuts on the political spending that is choking the Spanish economy.

Instead, nothing substantial has been done about the large subsidies and grants, duplicate government agencies and the unsustainable weight of a bloated state created on the back of the housing bubble.

“Government’s view of the economy could be summed up in a few short phrases: If it moves, tax it. If it keeps moving, regulate it. And if it stops moving, subsidize it.” Ronald Reagan

A government apparatus that is still above the peak levels of the bubble in 2007 has been cosmetically cut ever so slightly and those cuts are deferred throughout three years. As an example, of the 600 loss-making public enterprises that had to be closed, only two have been closed. No hurry. Meanwhile Spain became the fourth country in Europe with higher taxes .

I hear that the reason for these soft measures on spending is because the government “relies on exports” and expect that gross domestic product will not fall “as much as currently estimated”, and as such it will not be necessary to reduce the weight of the state, which is currently “only” 50 percent of the economy.In my opinion, Spain runs the risk of following in the footsteps of Portugal. “We’ve done our homework,” said Vitor Gaspar, Portugal’s finance minister. Yes, all but cutting the weight of political spending. In Portugal, the weight of the state in the economy rocketed and bond yields rose again after the cuts to historic highs.

The impact on the economy of constantly rescuing and subsidizing entities is brutal because it discourages the efficient, weakens the non-problematic companies and kills the perception of economic freedom, but above all, because it makes “socializing losses” a habit when it should be a truly exceptional measure and limited to extreme cases.

This is important because when we see that the €100bn “loan” to bail out banks includes the following demands:

– A clause that requires banks to have a capitalization (core capital) of 9 percent. This means a larger “credit crunch” than currently seen unless we liberate financial resources currently absorbed by the government, forcing banks to buy sovereign and subsidizing zombie companies.

– Requirement to divest industrial holdings. If tax increases, lack of security and regulatory uncertainty weaken companies, stocks collapse and capital losses of these holdings will be extreme.

– Requires the creation of “agencies to sell troubled assets” – bad banks – in which the taxpayer runs the risk that the price paid by the state for these assets is “far from a bargain.”

When public resources are allocated to bailouts and subsidies constantly and in numerous sectors the crowding-out effect not only hurts the real economy but it also forces taxpayers and investors out. Who will create wealth and tax revenues if we end up with a country of rescued banks and subsidized firms?

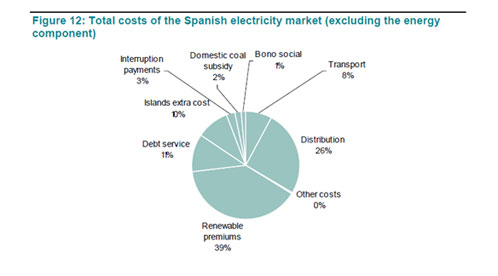

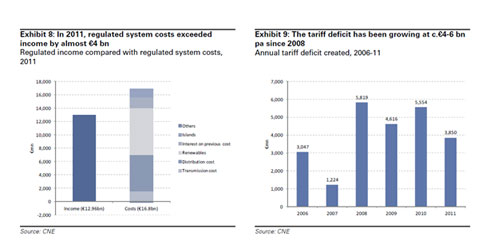

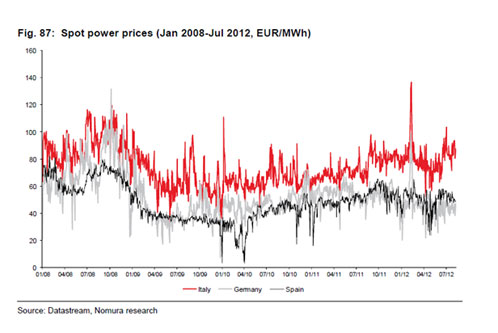

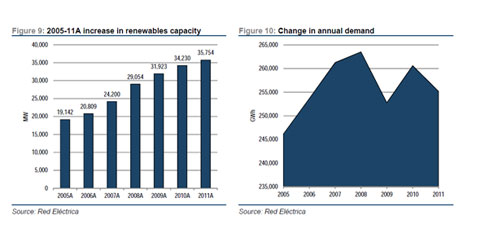

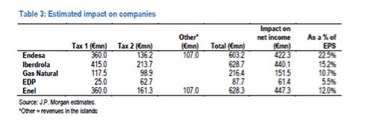

The electricity sector regulation that has been leaked seems equally wrong-footed, aiming to seize revenues from any company that generates positive cash flow. After a decade of planning as if demand were to grow by 2 percent per annum, giving subsidies everywhere. Now that the tariff deficit and the cost of the system have ballooned, the solution is to tax everyone with the risk of bankrupting the whole energy sector, which would be loss-making in generation and distribution in Spain.For reference, I wrote an article a few months ago about the numerous mistakes made by Spain in its energy policy called “The problem of fixing the price of electricity in government offices and not in the market.”

In a nutshell, we have a problem when most technologies are subsidized and over-capacity is not sorted through market dynamics. Subsidized coal, capacity payments, “restriction” markets, unsustainable premiums to renewables, etc. Overcapacity in the entire system… But who cares when the taxpayer pays for generous subsidies and planning mistakes?

We risk losing investors in Spanish debt and the Ibex 35

If we rescue the inefficient and those who eternally generate losses, we will continue pushing out investments and capital, hurting small and medium enterprises, which generate 70 percent of value added in our country, making it impossible for businesses to grow due to restrictive legislation, high energy costs and an onerous tax burden.The policy of “pretend and extend” of the government aims to help different lobbies, but the problem is that cronyism just makes zombie companies, not strong ones. As the government slowly runs out of other people’s money, even lobbies end up suffering the tax collection greed. Everybody loses.

The state cannot limit and supplant the private sector. Just looking at the average returns made by government investments in the past eight years is painful. Negative, on average, compared with the cost of capital.

The bank bailouts and unproductive subsidies are two very similar problems arising from the habit of governments of intervening in business decisions and then “try to solve” their mistakes through confiscatory measures. And it’s very easy to do when there is too much money available, but when the government runs out of other people’s money, funding inefficiency and subsidies means more debt.

And then we have a problem with 320 percent of GDP in private and public debt, 20 percent of the total private debt of Spain in the balance sheet of 15 companies of the Ibex, and refinancing needs in 2014 that account for 35 percent of the total “supply” of bonds in Europe.

We must stop intervening wildly. The solution for Spain cannot be trying and failing to recover the tax revenues from the real estate bubble, as I mentioned in this Wall Street Journal article.

I read that the Spanish government is very worried about the possibility that the companies in the Ibex 35 could be taken over. However, through a myriad of taxes, regulatory changes and legal uncertainty, Spain seems to be making its companies unattractive and weaker, massively indebted, uneconomic and subject to the whims of the state both from the investment side (“you have to build at any cost”) and from the side of profits, which are seized from time to time.

It is sad to say, but more and more funds are not allowed to invest in Spain. I hear it constantly. “Spain is uninvestable.” If I were a member of the government, I would worry less about trying to “protect” through intervention and I would worry more about attracting capital.

Recipe for a Spanish Comeback

(This article was published in The Wall Street Journal on June 26th, 2012 copyright WSJ)

According to Spanish Finance Minister Luis de Guindos, investors are not taking Spain’s “growth potential” into account. There is truth in that assessment, but Spanish authorities seem resigned to the notion that they can do no more to actualize this “potential.” I believe there is a lot more they could do.Given its potential, Spain can do better, it can do more and it can do it now.

Sovereign-bond investors are by definition the most risk-averse of the world’s financiers. Markets want clarity, sustainability and no surprises. Spain needs to prove to them that it can not only meet its current economic estimates, but beat them. The country has done it many times in the past, and it still possesses all that “potential” that Mr. de Guindos talked about. Spain can do better, it can do more and it can do it now.copyright The Wall Street Journal. Published with permission.