(This article was published in Spanish in Cotizalia.com on March 4th 2010)

For several months we have been listening to our governments talk of the goal of achieving the so-called “energy independence”, defined as absence of outsourcing of energy supplies given energy dependence on countries that are”not friends”, mainly the Middle East, is “bad” for the economy and security of supply. Truly outrageous.

Just looking at the different energy plans of OECD countries allows us to realize the political and strategic error of using aggressive rhetoric against producing countries. Indeed, the most optimistic of predictions of installation of renewable energy will not reduce the use of fossil fuels aggressively.

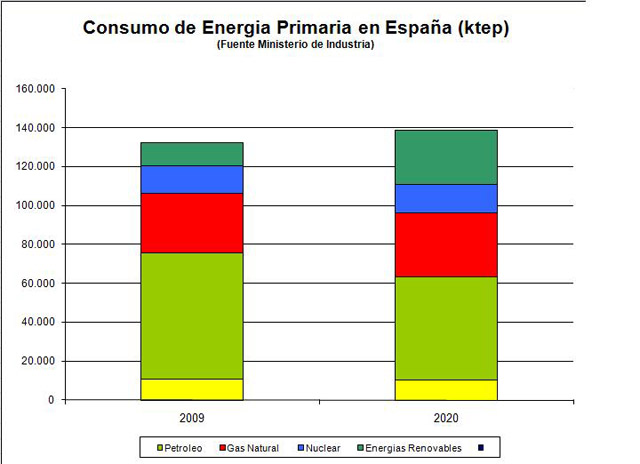

In Spain, for example, a country leader in renewable energy, we continue to import 1.1 million barrels a day, and the Government in a document published on March 1, estimates that in 2020 oil will remain at 38% of primary energy consumption , and natural gas by 23%. At European level the figure is very similar, 40% and 26%.

A study by Richard Heiberg (“Searching for aMiracle”) for the International Forum on Globalization, states that “Present expectations for new technological replacements are probably overly optimistic with regard to ecological sustainability, potential scale of development, and levels of ‘net energy’ gain — i.e., the amount of energy actually yielded once energy inputs for the production process have been subtracted”

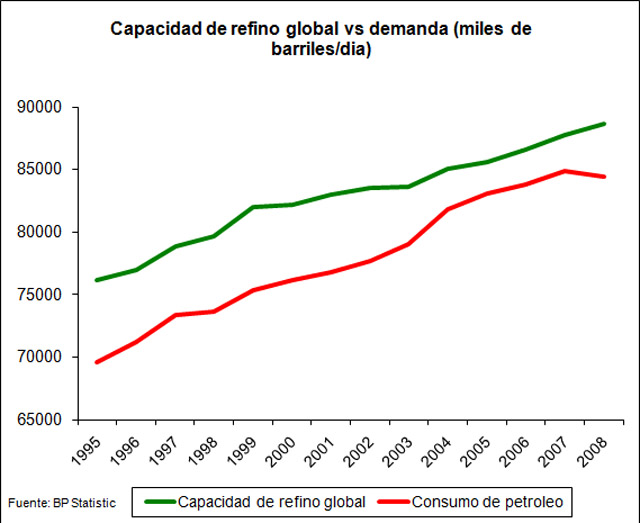

This is not to deny or attack the innovation and the importance of alternative energy, essential to meet the needs of a globalized world where per capita energy demand in non-OECD countries will grow from 5 barrels of oil equivalent per day to 25 barrels equivalent per day in twenty years. Moreover, the argument of the gradual depletion of nature reserves is valid, although on a longer timeframe than some “peak oil” theorists would like to believe. This is about warning of the economic and strategic risks of this policy of negative rhetoric and to avoid losing competitiveness.

Economically, aiming for energy independence is not justifiable in the long term. The alternative energy bill in the EU exceeds $180 per barrel equivalent and is now between 1.7 and 2.3% of GDP in various OECD countries, considering only subsidies and grants. In its energy plan, the Spanish government estimates an additional cost from renewable subsidies of between €3.66bn and €7.42bn in 2011 (the equivalent of the entire country’s oil imports at $100-190/bbl). In addition, the wind blows when it wants to and solar is not viable as an alternative in a massive scale. Of course, hydropower is not enough either because it is also unpredictable. And at this point it is pointless to even think about building nuclear plants to fill the gap in fossil energy because it would be impossible to achieve in at least 65 years.

The Spanish Ministry of Industry in its plan published on March 1st says the following about the extra cost created by the need to increase premiums on alternative energy:

a) It does not quantify the benefits in employment, which has not been demonstrated in a country that builds 1.5 GW per year, where the alternative energy sector suffers from overcapacity and has virtually the same employees as in 2006),

b) It improves the balance of payments, which is not evident either since the technologies are predominantly foreign, so we switch from paying to producing countries to pay to Vestas, Siemens, First Solar and General Electric,

c) Benefits in CO2 reduction, which has not been proven either as the countries have barely reduced their emissions and continue to subsidize domestic coal and lignite.

Therefore, the only way to justify the extra cost is to estimate an annual GDP growth above 3% between 2010 and 2020. Scary.

Strategically, the impossibility of sharply reducing imports of fossil fuels, even assuming increased efficiency of 1.5-2% annually, as estimated by the US Secretary of State for Energy state, makes the rhetoric of “independence” highly dangerous. It does not seem advisable to me to “threaten” our suppliers and partners when the most optimistic outlook for the OECD countries continues to envisage between 30 and 50% of our primary energy consumption from fossil fuels. Additionally, the argument that the suppliers of oil, coal and gas are not reliable is not acceptable and. Pure economic xenophobia. There has been more interventionism, nationalism, supply cuts and interconnection problems among European countries and the US than nationalization in Venezuela, Bolivia or Iran. As an example, Spain has suffered decades of supply cuts from France and never one issue with Algeria. The UK has had more issues with gas supplies from Norway than from any Middle Eastern supplier.

I find it ironic to hear our governments demand from producing countries more investments, more contracts for our companies and more production while we threaten them with tendentious arguments about energy independence. Russia, India and China are betting on all forms of energy while still bet on the importance natural resources. Meanwhile in other countries we can continue to argue in favor of energy independence, but we are shooting ourselves in the foot. Just wait and see.