‘The question is not whether there will be a military action against Syria. The questions are “who?”, “What?”, and “when”? ‘ – SocGen Analyst

In 1973, Hafez Al-Assad was the president of Syria . Between that year and 1982 the regime conducted a systematic terror campaign against the opposition, which led to the slaughter of up to 40,000 people after the rebellion of the city of Hama. Al-Assad remained in power until 2000, when he was succeeded by his son, Bashar , the current Syrian leader. During all those years, outrage and international criticism of the regime always ended in many words and little action.

Now we face a difficult situation. More than two years of civil confrontation, 100,000 dead according to the UN and a major geopolitical problem.

I have had the opportunity to travel several times to Damascus and the silence of the West against the excesses of the regime are very quickly explained walking down the streets. The secularization of Syrian society has always been seen as a major benefit compared to the problem of oppression and lack of freedom.

China , Russia and Iran support the regime of Bashar Al-Assad.

Russia’s position is logical. It has committed investments in the country exceeding $20 billion and is the largest supplier of military equipment to the country.

Implications for Western countries.

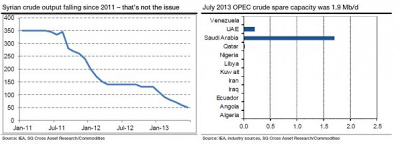

The attack on Syria, for the United States, United Kingdom and their allies is a difficult case of “damned if you do, damned if you don’t”. On the strategic side it is wasp nest, where it is not clear whether it is worth supporting an allegedly jihadist opposition, potentially close to Al-Qaeda, and it is difficult not to act agaisnt a regime that uses chemical weapons on the civil population. It is difficult to risk to create another conflict like Iraq when both sides in the Syria war can have negative implications for Western interests. It has become a choice of “lesser evil” in geopolitics. An issue explained in the excellent book by Michael Ignatieff , The Lesser Evil .On the economic side, Syria is not the potential benefit that Iraq was. Syria produces around 50,000 barrels per day and at the peak of 2011 it produced only 350,000 barrels/day, compared with 2.8 million barrels/day in Iraq.Syria, therefore, is irrelevant in terms of production, and its fields are not very attractive as an investment, with an average return of 10% at $ 100/barrel.Regarding the risk of supply… It’s very low. OPEC spare capacity is at a comfortable level of 1.9 million barrels/day, crude oil inventories in the OECD increased by 11.9 million barrels and 2.7 million barrels overall in July. Meanwhile, in the U.S., the domestic oil revolution has led the country to import less than 8 million barrels, the lowest amount in 17 years.

World oil supply grew by 575,000 barrels/day in July to 91.85 million barrels/day. There is no shortage of oil in any part of the system .

And if Syria is not a supply problem, why does the oil price rise?

Fundamentally due to an exaggerated perception of geopolitical risk, which adds a premium to the price of oil that was lost thanks to the revolution of shale oil in the United States.

An expectation of widespread conflict that has very little chance of happening. The famous Arab Spring had little impact on an extremely well supplied market, where Saudi Arabia and the OPEC countries with surplus capacity have more than covered the needs created by any bumps in production, including the embargo on Iran.

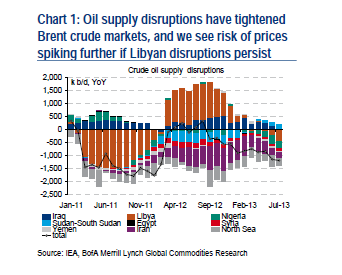

But there is also a fundamental element supporting a price above $ 100/barrel of Brent . Libyan oil exports have slumped to 330,000 barrels/day, less than half than expected, amid protests, strikes and shut-downs.

For some there is also a risk that the Syrian conflict revives the problems in Iraq , which has seen attacks in the northern pipeline. Many investors fear that Iran might promote attacks in southern Iraq, affecting two million barrels / day of exports in the port complex of Basrah. However, acquaintances and colleagues who work in the oil sector in Iraq doubt of that risk, and private security conducts extremely detailed track of everything that happens at the port. That is one reason why the port transactions are so slow in the south.

But fear is a powerful signal and it can make oil break the $ 120/barrel level, even go up to 140 dollars/barrel without a short-term fundamental justification.

The big question is if oil shoots up to $150/barrel, as some predict, what effect would it have on the global economy? The analysis I always make is that until the “oil burden” reaches 7.5-8% of global GDP, there is no significant impact. The “oil burden” is the amount of money spent on oil imports. Currently it’s less than 6%. And the “oil burden” is shrinking dramatically in the United States, for example, 17% so far this year.

What can affect economies is the cost of an attack on Syria, estimated at 13 million dollars a day, climbing to about 120 million a week if it’s a Libyan style attack, with another 800 million dollars to establish exclusion zones. Given that the United States will surpass the debt ceiling again in October -16.7 trillion – the cost is not an irrelevant issue.

As always, an environment of rising prices benefit oil service companies that increase their margins and profits, and independent production companies. As I have said for many years, be careful playing oil prices through the integrated European conglomerates , which generated a return on capital employed (ROCE) of 13% at $ 11/barrel and at $115/ barrel they publish exactly the same returns on investment. Because costs soar, companies lose production from concessions (apart from those who are exposed to Libya, because of production sharing contracts, where they receive less barrels when prices soar) and, of course, refining margins deteriorate.

An attack on Syria may happen this month. It may be limited. But what has always been clear is that these “quick and concentrated attacks” have always been far less limited and more extended in time-and cost than what is initially expected. We’ll see.

For the oil market, the crisis in Syria, as the Arab Spring, will again be a test of the strength of the supply machine. As in 2011, I’m sure it will surprise us positively. I do not foresee any supply problems.