Carl Icahn, uno de los grandes inversores del mundo, comenta que cuando se lanzó la primera ronda de expansión cuantitativa, el llamado QE, le preguntó a varios miembros de la Reserva Federal si sabían las consecuencias que podría tener un aumento de la masa monetaria de tal calibre. Y apuntó en una servilleta la respuesta. «No sabemos».

Hoy ya es evidente que los bancos centrales no imprimen crecimiento. El fracaso estrepitoso de Abenomics en Japón nos muestra que el gas de la risa monetario no soluciona problemas estructurales.

A la hora de valorar las políticas expansivas tendemos a olvidar que EEUU ha crecido y reducido el paro gracias, en gran parte, a encontrar petróleo y una revolución energética que he generado 2,5 millones de puestos de trabajo, y que la Unión Europea ya estaba recuperándose mucho antes de lanzar el programa de recompras del BCE. La política monetaria es una herramienta que, como todas,pierde efectividad si se abusa de ella o se olvidan las reformas estructurales, algo de lo que alerta constantemente Mario Draghi.

¿Nos encontramos en un entorno global de estancamiento secular? No es aun el caso. Pero claramente, ante un problema de saturación de deuda y sobrecapacidad industrial, nos enfrentamos a lo que yo llamo las tres Bs. Bajos tipos, baja inflación, bajo crecimiento.

Tras un aumento de la deuda global en los últimos siete años de más de 19 billones de dólares incluyendo un aumento del balance de los bancos centrales de más de cinco billones, podemos decir que el riesgo en las economías globales se encuentra en cuatro frentes interconectados entre ellos.

La ralentización de China presenta elementos positivos y negativos. Los positivos son evidentes. Como consumidor desproporcionado de materias primas, un cambio de modelo a una economía menos industrial y más de consumo es una gran noticia porque bajan los precios de las materias primas y el futuro es más sostenible. Por el lado negativo, la enorme sobrecapacidad -30%- de la economía china implica que el gigante asiático va a seguir exportando deflación -bajos precios- al resto del mundo y acelerando los desequilibrios de sus socios comerciales.

La guerra de divisas global, que -como las guerras entre bandas rivales- niega todo el mundo aunque sea evidente, tiene un impacto desacelerador muy importante. La política de «empobrecer al vecino» es una forma adicional de proteccionismo que no surte efecto y solo crea un efecto placebo a corto plazo. Pierde su dudosa efectividad cuando todos la llevan a cabo, pero sobre todo genera una enorme salida de capitales de las economías más dependientes de divisa extranjera.

La parada en seco de mercados emergentes. En 2015 será el primer ejercicio en mucho tiempo en el que veamos una salida neta de capitales de mercados emergentes liderada por el propio inversor doméstico. Adicionalmente, una década de políticas de demanda excesivas han llevado a países como Brasil a acumular desequilibrios muy relevantes que son difíciles de solventar a corto plazo puesto que se ha creado una sobrecapacidad muy similar a la creada en Europa entre 2004 y 2010, con planes industriales a todas luces optimistas.

Los bajos precios de las materias primas ponen a las economías de los países productores en enormes dificultades. En vez de aprovechar para diversificar sus economías, muchos han perdido años de ingresos extraordinarios por altos precios manteniendo un modelo económico rentista y de bajo valor añadido.

El impacto sobre la Eurozona de momento es relativamente moderado. Esta semana se han publicado los índices manufactureros y, a pesar de la desaceleración, continúan en territorio expansivo. A la Unión Europea, como a EEUU, le beneficia la salida de capitales de mercados emergentes hacia economías maduras y aparentemente más estables. Adicionalmente, el hecho de que la recuperación de la Unión Europea venga tras la generación de un superávit comercial récord es importantísimo. La Eurozona no se ha entregado a multiplicar los desequilibrios y cubrir el pinchazo de una burbuja creando otra, como se hizo con los planes de estímulo de 2008-2009. Que la recuperación venga de la aportación del sector exterior y se consiga sin aumentar la deuda total hace que los riesgos sean menores. Pero no irrelevantes.

El crecimiento del comercio global sigue ralentizándose y no es por casualidad. Hace muchos años que no se firman acuerdos bilaterales verdaderamente relevantes, y la represión financiera generalizada, bajar tipos y devaluar, no deja de ser una forma más de proteccionismo. Ello, añadido a la saturación de economíasemergentes«por políticas de demanda erróneas y endeudadas, tiene un impacto negativo global.

En España hemos visto como el Banco de España revisaba levemente a la baja las cifras de crecimiento, pero la economía mantiene un impulso en el que el aumento del consumo minorista aporta una gran parte del crecimiento del PIB, junto al sector exterior.

España importa más de lo que exporta a China o Brasil, con lo cual el impacto para nosotros de esas economías es bajo. De hecho nuestras exportaciones alcanzaron nivel récord y ganando cuota de mercado ya con varios países emergentes en clara desaceleración. En cualquier caso, a mí lo que me interesa es la aportación al PIB del sector exterior en su conjunto. Hablar de altas exportaciones cuando el déficit comercial se movía entre el 7% y el 9% del PIB como en el 2004-2008 era como felicitarse por agrandar el agujero con el exterior. En 2015 probablemente cerremos con superávit o cero déficit, y esa es una gran noticia cuando además está creciendo la inversión productiva.

Por otro lado, España y la Eurozona siguen beneficiándose más de la caída de las materias primas, como importadores netos, que el impacto negativo de la desaceleración global. El acceso a financiación no es un riesgo, con un BCE que se plantea aumentar su programa de recompras, según Standard and Poor’s.

Los riesgos en España son, por lo tanto, fundamentalmente internos. El riesgo de abandonar las reformas y volver a llevar a cabo las políticas que nos llevaron a estar al borde de la quiebra, la aterradora llamada a «estimular la demanda interna» desde la financiación de planes públicos y elefantes blancos, es enorme. Preocupa la falta de arrepentimiento de los que llevaron a cabo en nuestro país elmayor desajuste visto en la OCDE en menor tiempo, que alcanzó 15 puntos del PIB entre desequilibrio fiscal y comercial. Preocupa aún más que se proponga repetir la misma política suicida, o, lo que es peor, que se alcancen coaliciones con partidos que no solo no admiten la locura de las apuestas populistas, sino que, ante la evidencia del fracaso en Brasil, Grecia, Argentina, Venezuela, acuden a culpar a cualquier enemigo exterior inventado para continuar aplicándolas.

España es un país que puede crecer mucho más y crear más empleo a pesar de esos riesgos globales. Lo hicimos en el pasado con crisis realmente graves a nivel internacional. Aumentando las rigideces, la intervención y copiando modelos estancados o recesivos como el dirigismo intervencionista no se va acelerar el crecimiento y, desde luego, no se va a hacer más sostenible. Tirando de la chequera en blanco y repitiendo los errores de 2006 solo vamos a conseguir… La crisis que vino después.

Pensar que aplicando las mismas fórmulas erróneas que han llevado a países de nuestro entorno a estancarse vamos a llegar a un resultado distinto es más que ingenuo. Es peligroso.

Precisamente ante un entorno global incierto y complejo la mejor manera de fortalecerse es seguir con las reformas, como el propio Draghi repite una y otra vez, profundizar en un modelo de crecimiento que no tire de deuda y sectores de bajo valor añadido, y sobre todo no acudir al canto de sirena de «incentivar» la demanda interna creando mayor sobrecapacidad y deuda de la que ya tenemos, que no es poca. Eso nos hará más fuertes.

Asumir que no hay un problema de sobrecapacidad sino de demanda es simplemente incorrecto. La sobrecapacidad industrial ya era del 18% antes de la crisis. Y no hay más que ver los mismos errores en países muy diversos.

Llevamos décadas de políticas de demanda y la saturación es evidente. Ahora toca devolver a las empresas y los ciudadanos el potencial de crecer más y mejor.

España necesita inversión real productiva, no Planes E. Miles de empresas más, y mucho capital para continuar cambiando el patrón de crecimiento y crear empleo desde el valor añadido, no de la decisión de un comité. Debería ser una prioridad que nuestro país recuperase urgentemente puestos en el ranking del Banco Mundial de Facilidad para Crear Empresas y de Libertad Económica, donde ocupamos puestos inaceptables para el potencial de nuestra economía.

En un entorno global complejo, debemos mostrar al mundo que somos el país donde merece la pena invertir, y hacerlo a largo plazo, para que el empleo sea mejor y de mayor calidad. La oportunidad, por lo tanto, es enorme ante un futuro incierto en el que el inversor busca economías seguras y fiables por encima de cuestionables crecimientos estratosféricos. Si ponemos palos en nuestras propias ruedas, perderemos esa oportunidad.

@elmundo

Daniel Lacalle es economista, director de inversiones de Tressis Gestión y autor deViaje a la Libertad Económica, La Madre de Todas las Batallas y Hablando se Entiende la Gente (con Emilio Ontiveros y Juan Torres)

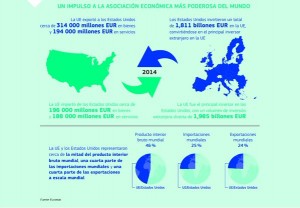

El TTIP no beneficia a las multinacionales, sino a las PyMEs exportadoras. Las multinacionales no necesitan acuerdos bilaterales porque pueden costearse abogados y asesores para entender las exigencias administrativas de los países. Los que se benefician de la armonización son los que no pueden pagar esas facturas. Acusar de ir contra el medio ambiente es cuando menos infantil, ya que la legislación europea no se vería afectada.

El TTIP no beneficia a las multinacionales, sino a las PyMEs exportadoras. Las multinacionales no necesitan acuerdos bilaterales porque pueden costearse abogados y asesores para entender las exigencias administrativas de los países. Los que se benefician de la armonización son los que no pueden pagar esas facturas. Acusar de ir contra el medio ambiente es cuando menos infantil, ya que la legislación europea no se vería afectada.